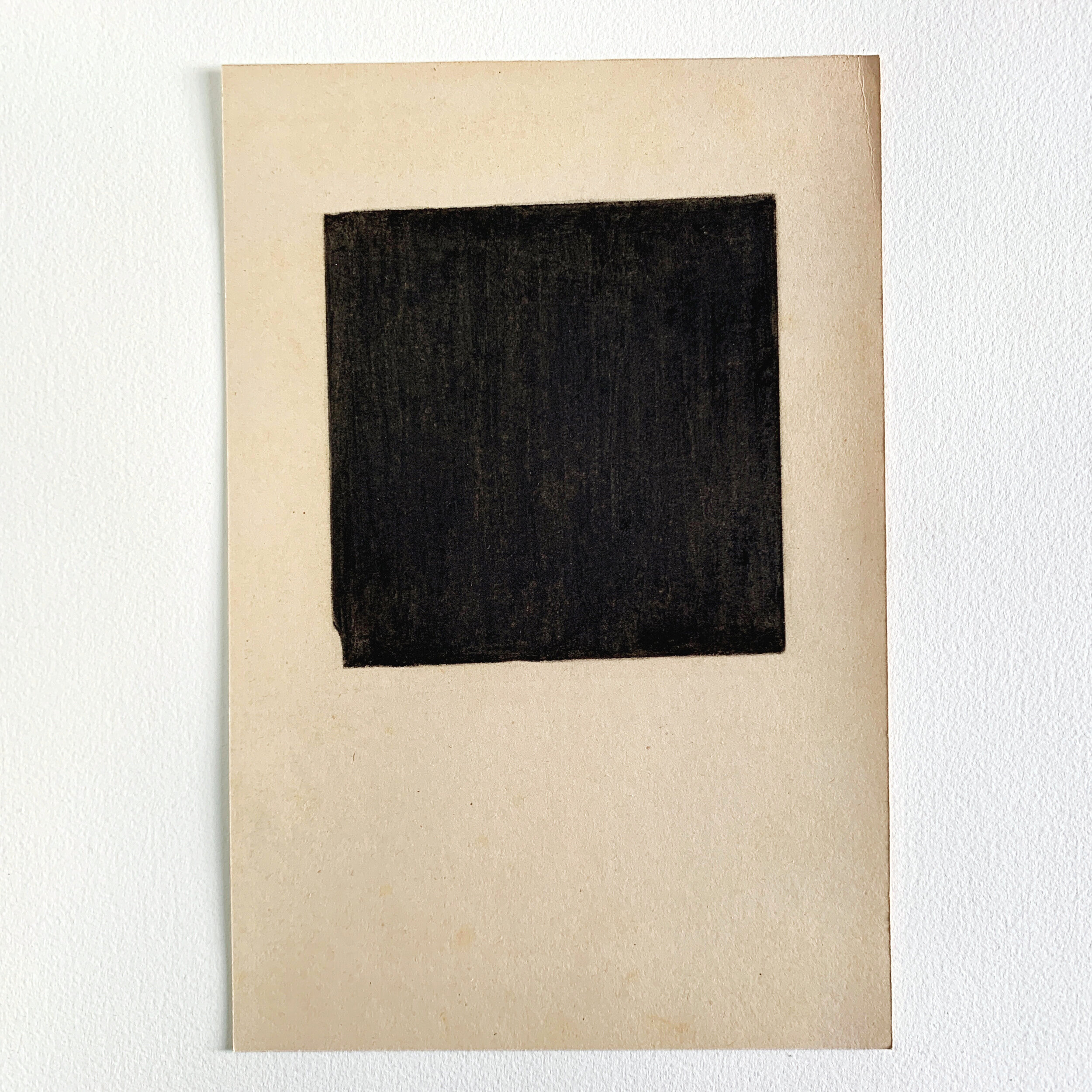

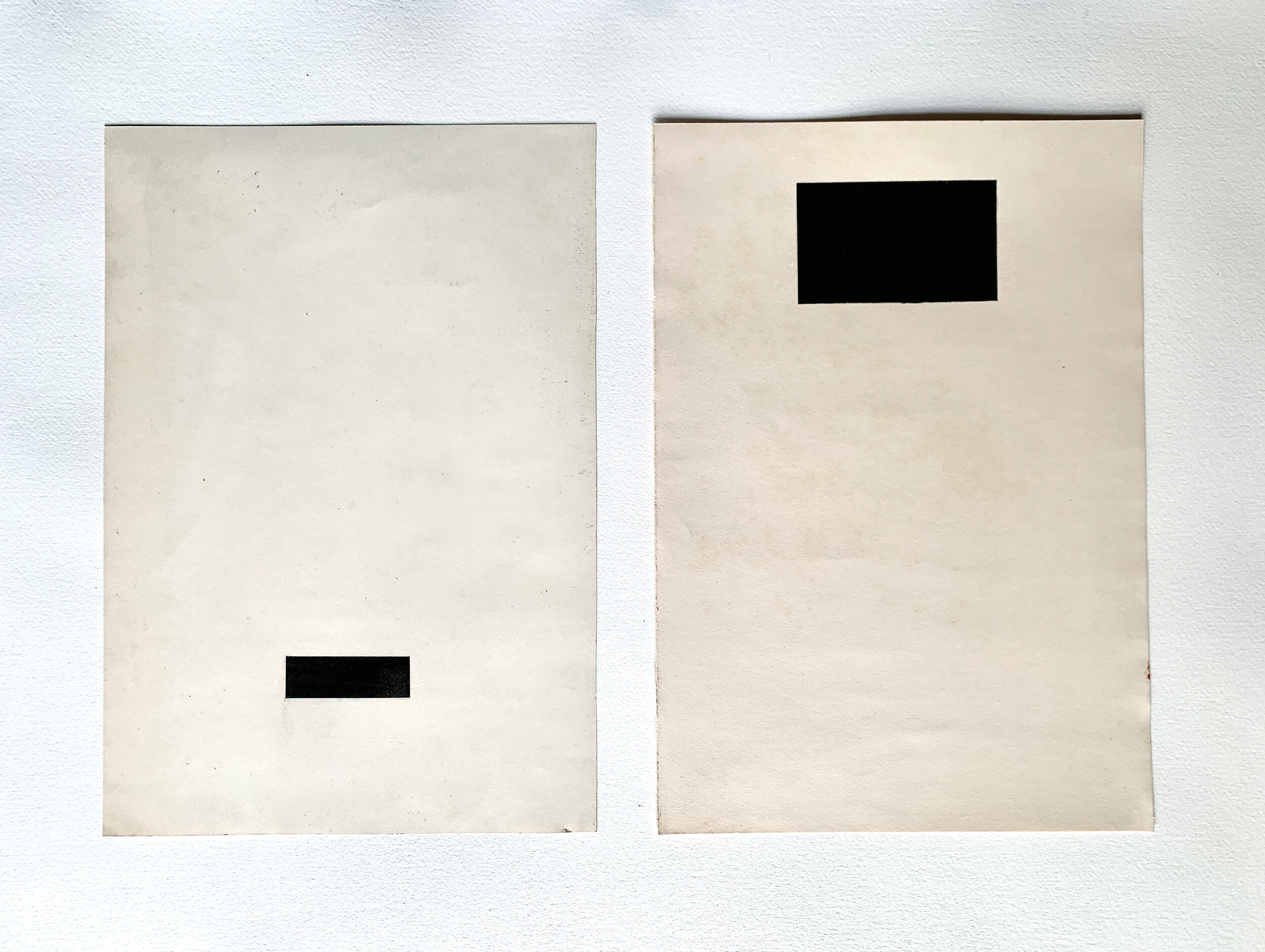

The progenitor of all subsequent black squares appears in Fludd’s Utriusque Cosmi Maioris Scilicet et Minoris Metaphysica, Physica Atque Technica Historia (Macrocosm Microcosm) published by Oppenheim (1617). Three versions all based on how it appears in the first edition of 1617 to match the original page and square dimensions:

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

300 x 200mm and 138 x 138mm.

2022.

Available

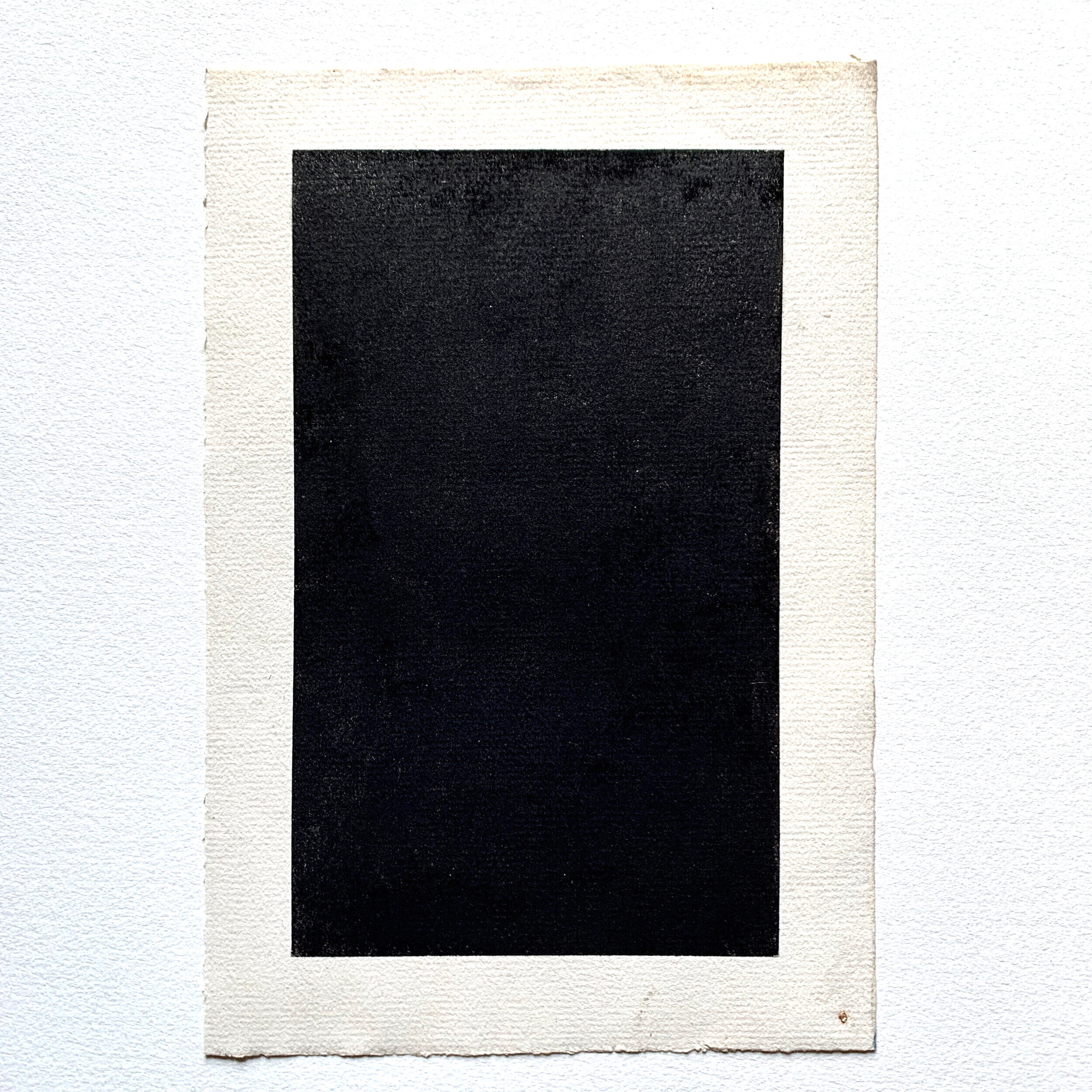

Referencing the minor tradition of ‘mourning pages’ in certain elegiac texts Sterne included a black page in the first volume of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759) in which Parson Yorick – a fictionalised self portrait of the author – dies.

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

Two versions matching the first edition of 1759: Octavo (228 x 152mm)

2022.

Available

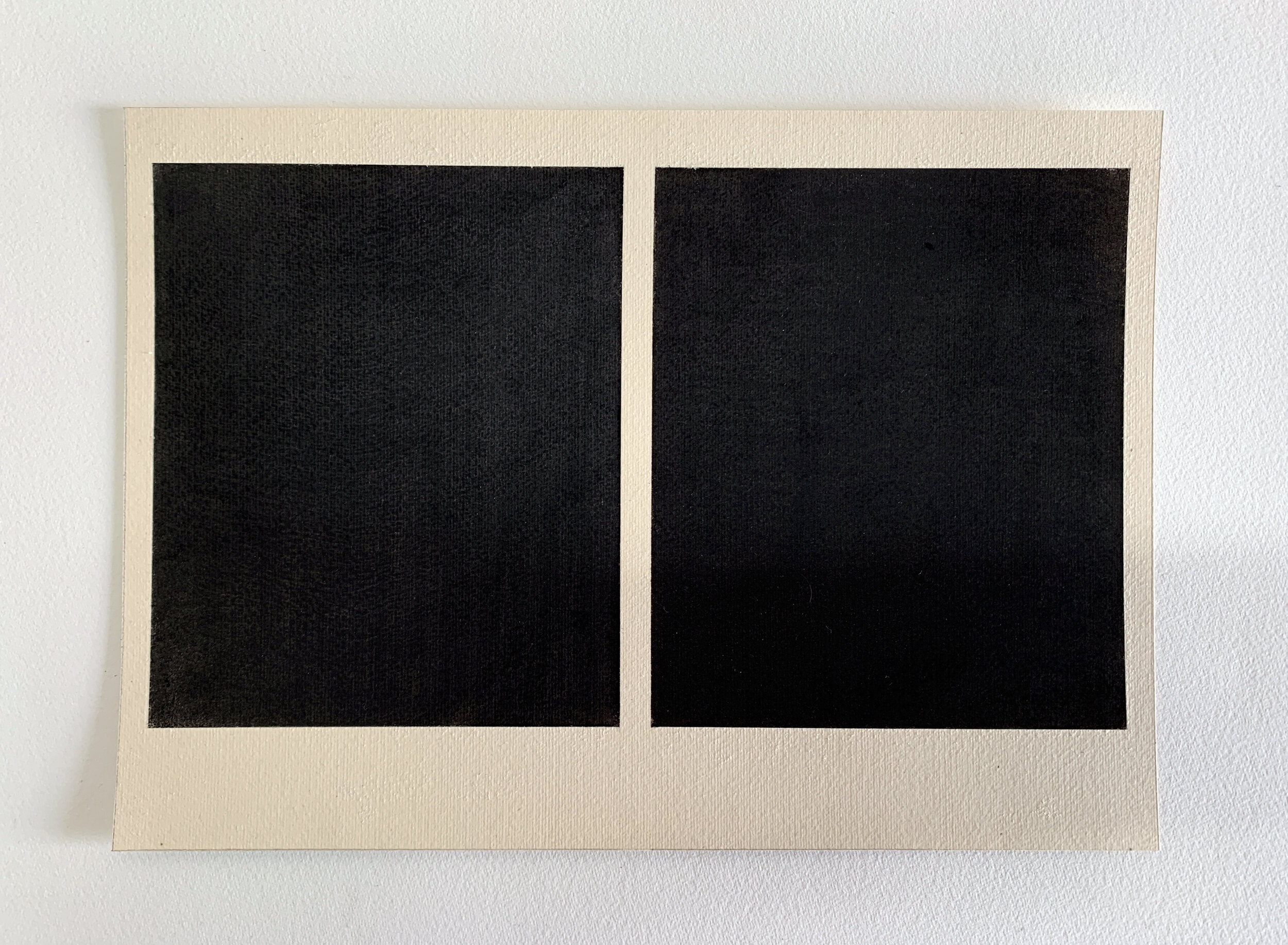

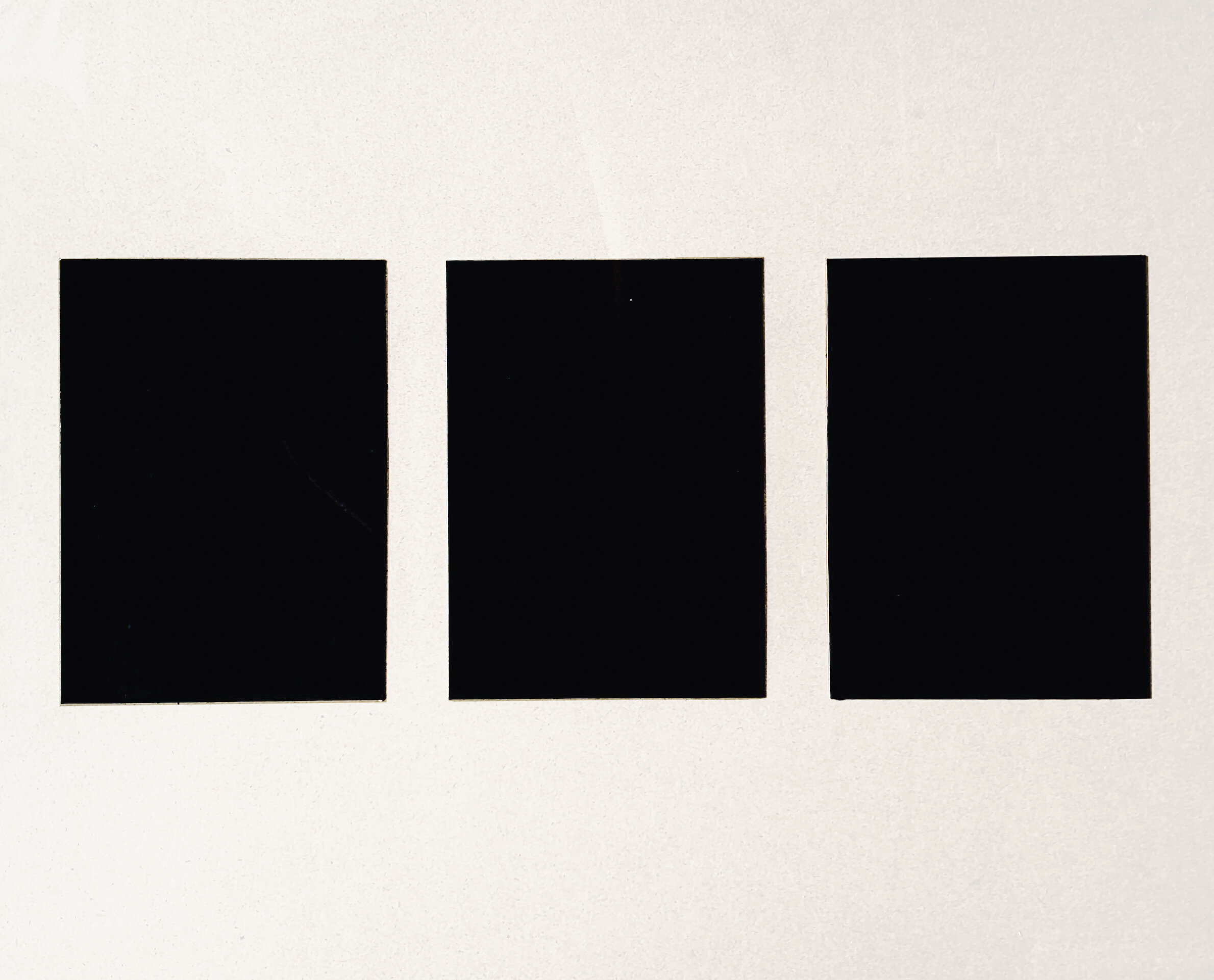

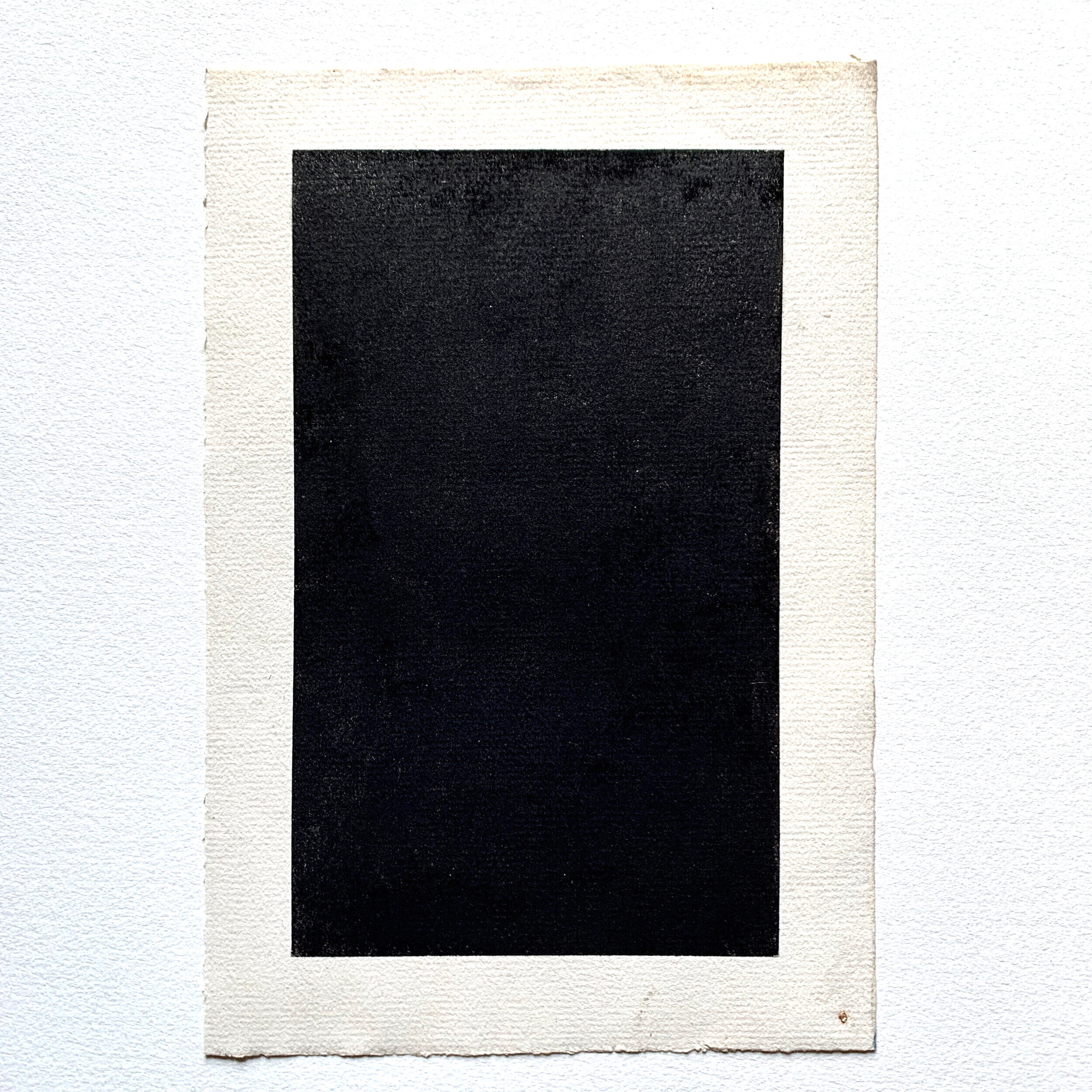

In tracing the historical appearance of ‘The Black Square’ and in attempting to record its occurrence in chronological order I have had to retrace my steps, occasionally coming across an important instance in the chain.

Prior to its use by Laurence Sterne in Tristram Shandy it was used elegiacally. Sterne set a precedent in which it came to be used as a satirical, humorous or absurdist device.

Throughout the 19thC in France there is a sequence of such instances beginning with Cham’s ‘Histoire de Monsieur Lajaunisse’, 1839. The two panels here have the following captions: ‘L, having extinguished his candle returns to his bed in complete darkness’ ‘L can’t understand it. He has no pillows or covers and his mattress is as hard as a bench’

As we shall see this tradition continues up to and including Malevich’s now notorious hidden text in ‘Black Square on a White Round’ of 1915.

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

250 x 160mm.

2022.

Available

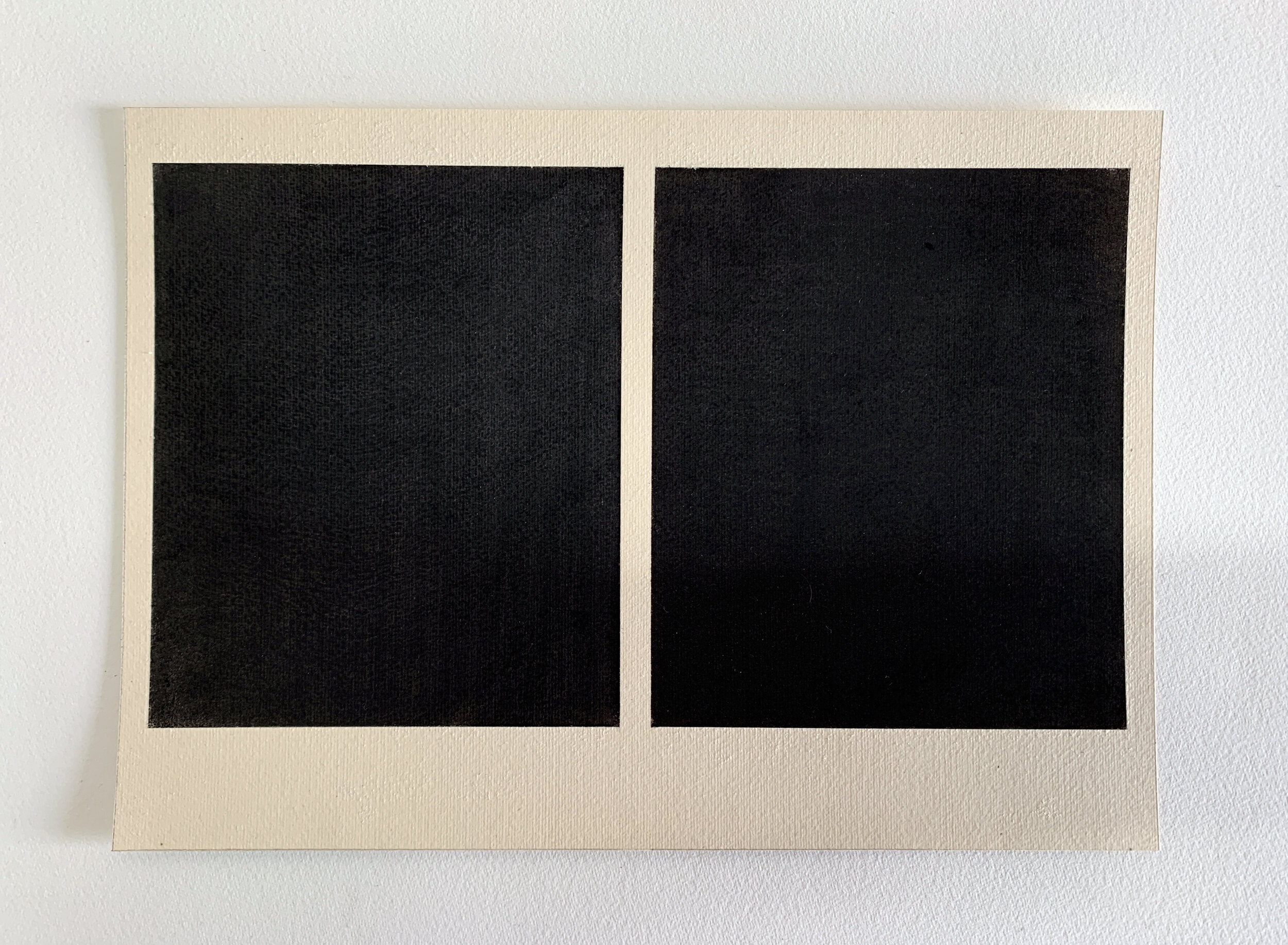

Diptych

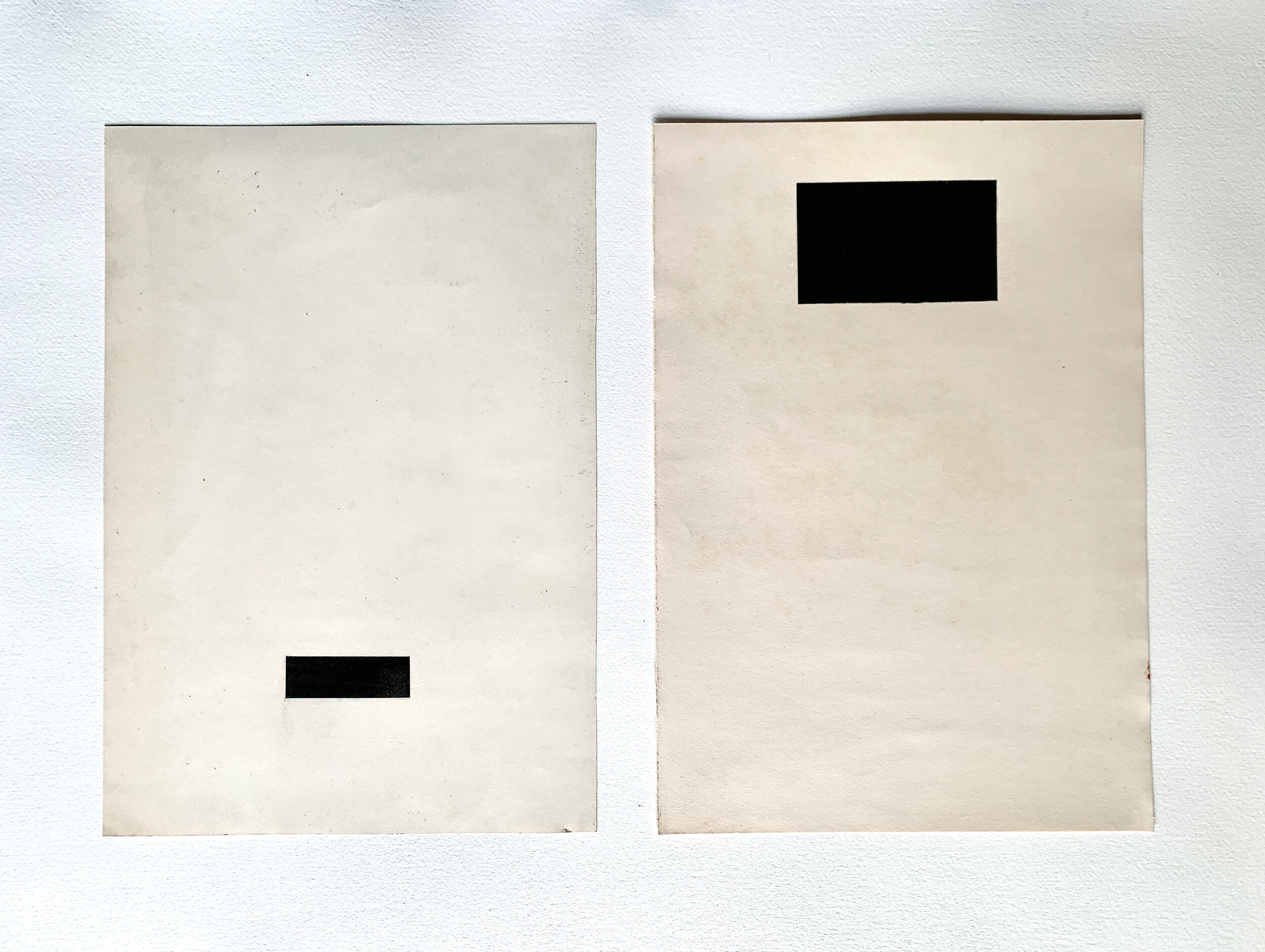

Left Panel; After Pelez: ‘Effet de nuit qui n’est pas Claire de lune’, La Charivari, 19th March 1843

Right Panel; After Bertall: ‘Vue de La Hogue (effet de nuit) ((Jean-Louis Petit)), La Salon de 1843, August 1843.

The blank or rather black panel as a satirical device appears twice in 1843. Both times it is used comment upon what were simply dark paintings.

Nocturne as a term for and later a genre in painting occurs later in the nineteenth century. These two caricatures of actual paintings exhibited at the Salon of 1843 pass comment on paintings that were considered incomprehensible.

Pelez’s illustration in La Charivari on the ‘initial impressions of La Salon’ and later that year Bertall’s illustrated volume; a complete satirical revue of the salon further the visual convention and meaning of the black square .

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

Page/Panel size: Each 36x26cm

2022.

Available

From ‘Histoire pittoresque, dramatique et caricaturale de la Sainte Russie d’apres les chroniqueurs et historiens Nestor, Nikan, Sylvestre, Karamsin, Segur, etc’ Paris, 1854.

Doré’s History of Holy Russia begins with a void, a black square and one can draw the analogy that Malevich’s ‘Black Square on a White Ground’ thus marks the end of that history; that it begins and ends with the ineffable: in the void.

Doré’s History is comprised of 500 loosely sequential images and was intended as both satire and anti-Russian propaganda during the Crimean War in which France and Russia were adversaries.

As such , the opening image of a black square is a very pointed ‘black mark’ against Russia.

As with all of these early instances I have reproduced the black square as it appears upon the page of the original publication.

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

Page size: 298 x 203mm.

2022.

Available

Bilhaud exhibited his dubiously titled all black painting in the Salon des Incohérents in 1882. It is the first fully monochrome or ‘monochroidal’ painting.

While the painting appears to be lost we know of its existence since it is directly referenced in the next instance in this sequence by Alphonse Allias.

If Combat de Négres, created by a humourist, was merely an absurdist joke (and one which as demonstrated in this series has a clear lineage) then it is remarkable that it did not wear thin sooner.

Again, the black square appears at a pivotal moment in history. In 1882, in his critique of the Enlightenment; ‘The Gay Science’, Friedrich Nietzsche declares the God is dead. In this context and, again, reaching its apogee in Malevich’s Black Square becomes significant of an age of ‘endarkenment’. I have inscribed beneath the charcoal my own, more apt title, a quote from Robert Pogue Harrison’s ‘Forests – The Shadow of Civilization’: ‘For all its glory, civilization cannot console us for the loss of what it destroys’

To arrive at appropriate dimensions for this piece I have referenced Alphonse Allias reproduction. It is thus a picture of a picture of a picture.

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

360 x 170mm.

2022.

Available

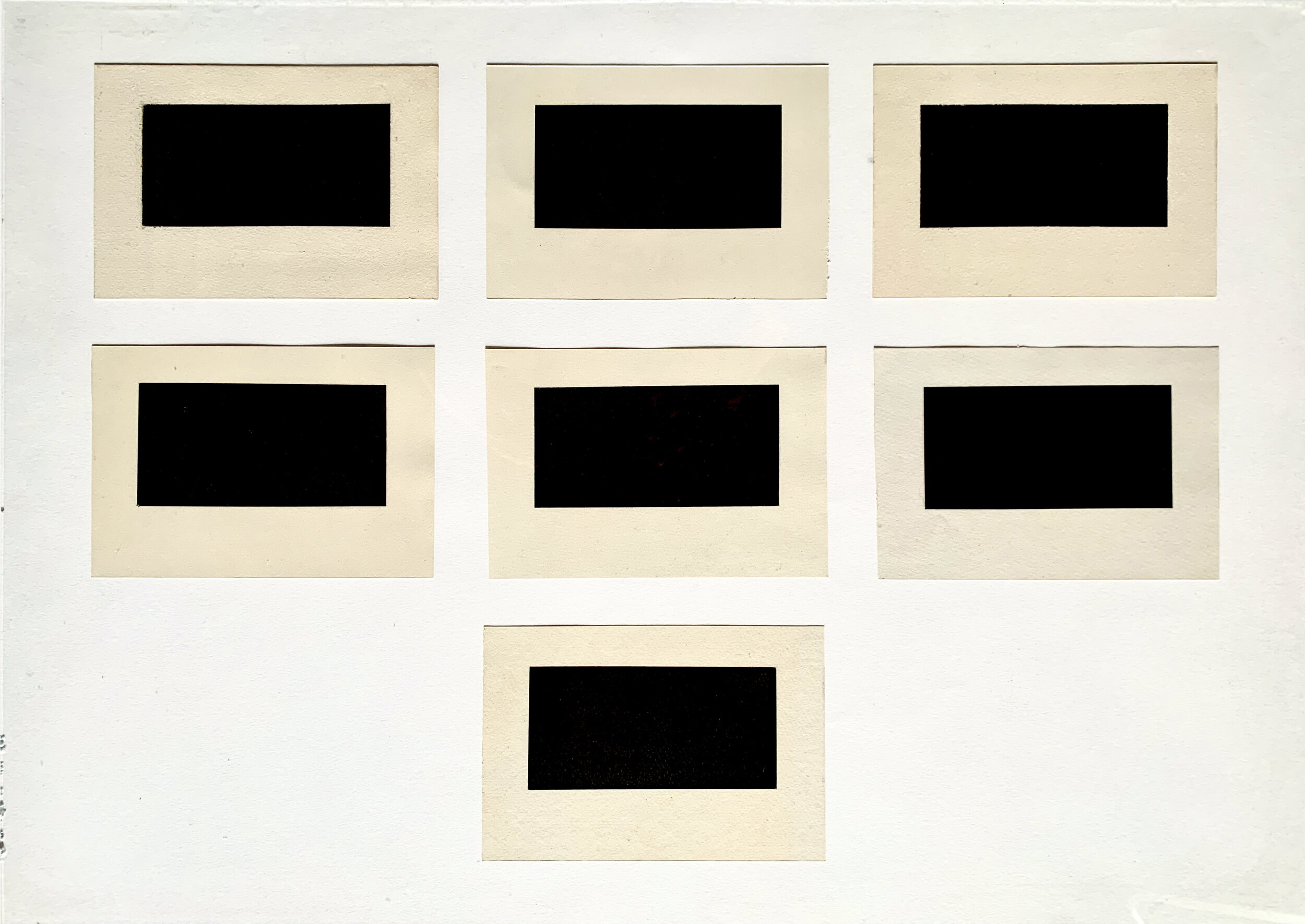

The inscription under Malevich’s Black Square on a White Ground, discovered in 2015: "Battle of negroes in a dark cave" appears to directly reference the caption to accompany the black monochrome in Allais’ absurdist ‘April Foolish Album’; “Combat de Nègres dans une cave pendant la nuit”

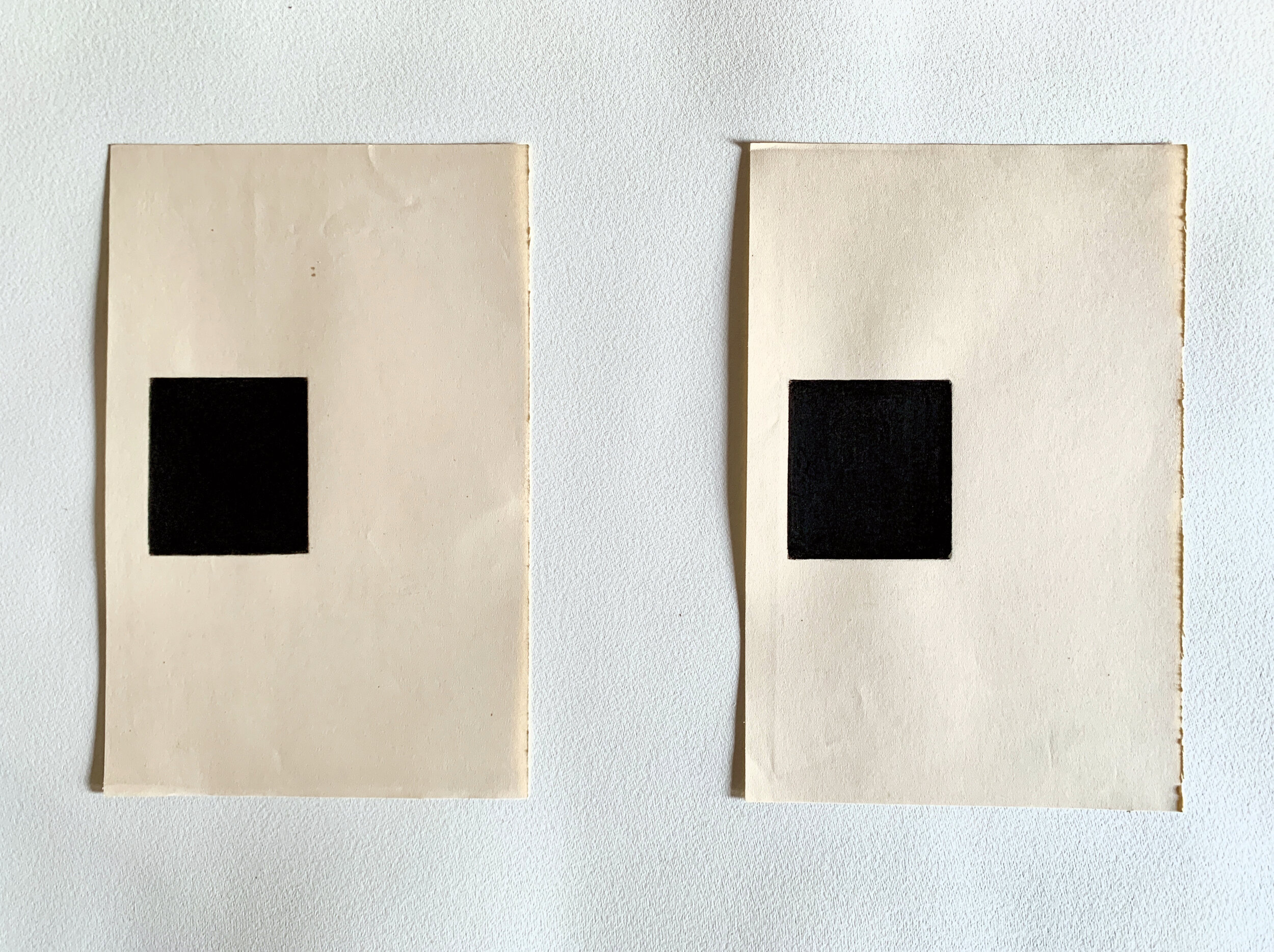

The Album is a monograph consisting of seven differently coloured monochrome plates and a score for a silent funeral march.

The seven captions can be found here :

https://www.wikiart.org/en/alphonse-allais/all-works#!#filterName:all-paintings-chronologically,resultType:masonry

Allais’ black plate in this volume directly references the previous instance in the sequence of black squares. Allais’ version is the only known illustration of Bilhaud’s black canvas. To arrive at the size and proportions of my recreation of Bilhaud’s image I added the sum of the areas of Allais’ seven coloured monochromes, while also rendering each black; thereby arriving at an equalization of both form and content.

Read in this, the original context, Malevich’s quotation of Allais’ caption for the colour black is less abhorrent than at first it appears. It is at odds with Malevich’s stated unitarian intentions for, and inspiration behind his arrival at The Black Square. However a retrospective reading of it that takes the quote into account does not truly reflect those intentions since at no stage does he reveal, title or write about this hidden inscription. What it does reveal is that Malevich’s Black Square is deadly serious but not necessarily somber - it carries and transmits the absurdity of life in a forest of symbols.

The hidden inscription and title for this heptatych derives from Plato’s Allegory of the Cave from The Republic: VII 517 a) in which a willed ignorance seems to triumph over elucidation. ‘In total darkness all things are equal’

Seven panels, each 124x185mm.

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper, 2022.

Available

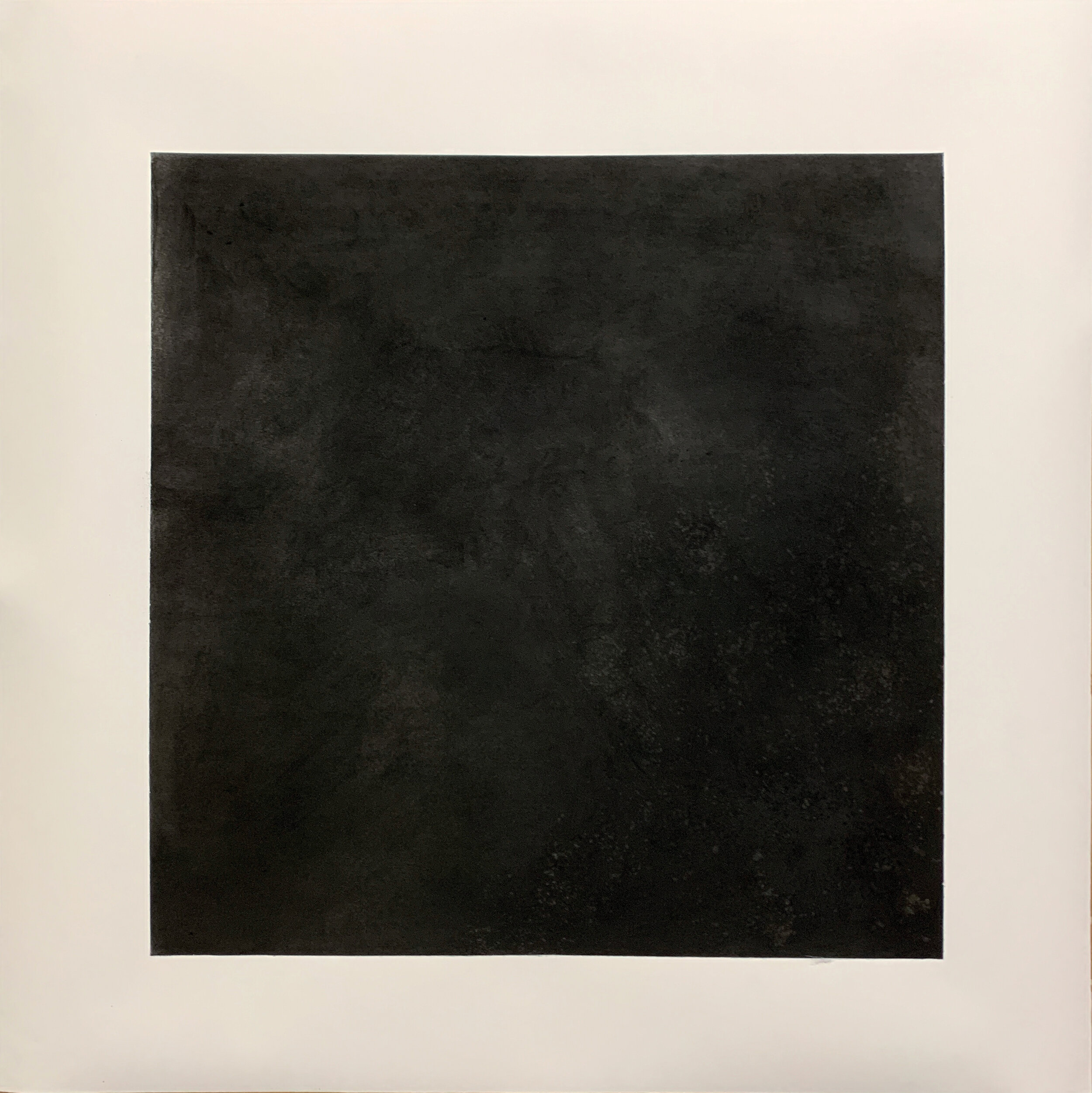

‘Whereof One Cannot Speak, Therof One Must Be Silent’

Wittgenstein’s aphorism (from Tractatus Logic-Philosophicus) along with Einstein’s aphoristic equation and Rutherford’s splitting of the atom all arrive during a short span of human history, in the blink of an eye.

Nature, now firmly in humanity’s facile grasp, is being prised open to reveal its innermost secrets: The übermensch has arrived and the will to power - at the expense of millions of lives– scourges the earth.

Malevich’s move towards his own ‘zero of form’ has its inception in his designs for the Russian Futurist opera “Victory over the Sun’ of 1913.

With his first ‘Black Square’ Malevich arrives at, as Tatiana Tolstaya has described it: ‘that critical, mysterious, coveted point after which, because of which and beyond which nothing exists and nothing can exist’. It is simultaneously a summation, conjoinment, apogee and a negation of all icons, all referential and reverential visual forms of communication. But it is not mute: it addresses directly, defiantly the ever receding and insubstantial void from which we came and to which we shall return.

It is both a curse and a liberation, and as we shall see we must be careful not to be burnt by the sun as we capture it.

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

79.5 x 79.5 cm

2022.

Available

‘Madmen who ceaselessly complain of nature, learn that all your evils arise from yourselves’ (JJ Rousseau)

The second version of Malevich’s Black Square was painted in 1923 and made to be exhibited at the Venice Biennale the following year.

The Black Square of 1923 was shipped to Venice with ‘Black Circle’ and ‘Black Cross’ and appeared in the catalogue but it seems they were never shown: Various sources attest to this and what is clear from these is that Malevich’s Suprematist work was not regarded as representative of Soviet art by the officials in charge of the Russian pavilion.

By this time Malevich was the principal of the State Institute of Artistic Culture in Petrograd (St Petersburg) and although previously an active member of the revolutionary art committees by 1923/4, and with the death of Lenin, the shift towards an official Socialist Realism under Stalin had begun.

The 1923 Black Square is the largest of the four versions Malevich painted.

My intention was to complete and exhibit all the works of this series together. That might still happen (since I can replicate works) but in the current situation these are all for sale. If interested in this or any other of the series send me a PM to enquire

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

106 x 106 cm.

2022.

“The Sublime Void’

A total eclipse ... and then came the ice of Stalinism crushing the cultural avant-garde: The ‘Victory Over the Sun’ desired by the Russian Futurists, this revolutionary tearing of the veil of the old order summoned the void; something inchoate, inexpressible and beyond reason: Zaum.

If ‘the painters task is to discover things not seen … presenting to plain sight what does not actually exist’ then painting could unite lowly manual labour with lofty mental conception and span the gap between the visible world and the immaterial realm.

As Hans Belting describes it there is an historical shift between intra-mission and extra-mission: between what we receive through perception and what we project through imagination, or belief. Malevich asks us to ‘swim into the abyss’ to exist between the two states. That the Black Square; such an absolute, concrete image should become the significant of this is no accident: it is the emblem of the certainty of uncertainty - both of the void and a barrier and it is up to us to discern which it represents for us and us alone.

Thus Joseph Conrad’s dictum: ‘the discovery of new values in life is a very chaotic experience: there is …a momentary darkness’ and to paraphrase James Lovelock ‘no one can second guess the future’. These are the reasons why many feel the Black Square to be frightening.

By 1929 the Black Square has begun to multiply and replicate itself: It is as if it constitutes the new tabula rasa and the primary locus within which painting can now truly, honestly begin to address the absurdity of life.

Tatyana Tolstaya suggests that for all artists there is a’ pre-square’ phase but once they have stared unflinching into this void they become ‘post-square’ : that is to say truly an artist, at home in what Gaston Bachelard terms an intimate immensity.

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

79.5 x 79.5cm.

2022.

‘A Quintessence even from Nothingness’

John Donne

In late 1930 Malevich was arrested and imprisoned as Stalinism became ever more proscriptive of progressive art, ever more prescriptive in favour of Socialist Realism.

The arrest was, in part, due to his taking part in the 1927 Große Berliner Kunstausstellung. Hoping to return to Germany he left 73 paintings with Hugo Häring.

Those paintings were, over the years, dispersed and served to disseminate Malevich’s ouvre, reputation and influence, particularly via a major exhibition at MoMA in New York in 1936. This show lead directly to the formation of the American Abstract Artists Group.

The Black Square was Malevich’s emblem; an entirely modern Ikon and one that provided ‘an image for the longing that pervades human finitude’. This last version, a defiant rebuke, is his memorial, epitaph and testament. When he died in 1935 it was hung above his coffin, on the front of the funeral procession and mourners carried a banner with a Black Square. His tombstone (now lost), below an old oak tree in Nemchinokova was a stone cube with a Black Square.

Next we will move chronologically beyond the Malevich’s Black Squares: Art goes on generating art, every critical response is a rebirth or renascence - revivifying the work that prompted it. Evidently this is the case with Malevich’s Black Squares; both literally and figuratively this symbolic ‘quintessence even from nothingness’ has reverberated down the years to our own epochal moment.

It is precisely in this, our own global period of darkness that new values must be found and while ‘The discovery of new values in life is a very chaotic experience, there is a momentary feeling of darkness’ … upon our emergence from it ‘we may be as close to a better world as we will ever come’ and we will require an equally potent banner.

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

53.5 x 53.5cm.

2022.

Available

Between the dark void from whence we came and to which we will all return - Hegel called this condition ‘that undifferentiated night in which, as we say, all cows are black’ there is the world: the stage upon which we, if we are fortunate, through seven acts, play our roles: Life as mere ephemeral drama. What comes before and after is unknowable.

If life is but ‘sound and fury’ signifying nothing then the ‘nothing‘ that is, by it’s absence, defined is the disordered void: chaos.

However, without darkness there can be no light; darkness is the precondition of it. The silent, expectant darkness of the stage, the cinema or the screen is the necessary context in which life is framed and represented as drama; teleological being as opposed to meaningless nothingness.

As we sit in atomized confinement within our own personal Camera Obscuras, our screens become the apertures through which we watch the unfolding drama of Covid 19. Each night we take to our balconies and windows to applaud the principal actors in this absurd and surreal roman à clef while we look upon an empty stage; the city streets, squares and parks that were until recently our stage where we were the principal actors in our own lives.

In 1928 Man Ray Directed ‘L'Étoile de Mer’, written by surrealist poet and writer Robert Desnos. Man Ray gave Desnos a photo with the dedication written on the white mount: ‘To Robert Desnos, lots of things that absorb light’. This ‘rayograph’; executed in a dark room is a contradiction: the image would be white if was indeed an exposure of things that absorb light. Yet it alludes to the tradition of the matte in theatre and cinema: the structural device with which the acts and scenes of a play or film begin, are divided and ultimately fade to black.

Night falls, the sun also rises.

Three panels/acts:

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

Each 23.9 x 17.8 cm

2022.

Available

‘The Tyger and the Phoenix’

May 1933: Darkness descends as a crowd gathers in Bebelplatz in Berlin. Soon, eyes begin to glitter and shine with the fervour of zealots.

It is said that knowledge is power but what of the power of willed ignorance bought forth by the deliberate, symbolic destruction of knowledge?

The ritual of purification enacted by the burning of recorded knowledge has but one aim: to draw from those flames ‘mind forg’d manacles’: mental slavery, and the history of this rite is exactly coterminous with that of recorded knowledge.

Only by a forced adherence to an orthodox truth, it seems, can there be any power over knowledge. By extinguishing the light of knowledge those that burn books exemplify the notion that ‘there is no necessary equation between light and enlightenment or lucidity’: In fact what is instilled by this ceremony is the belief in a reduced and rectified scripture: orthodoxy.

Man is otherwise perpetually L'Homme Foudroyé: Astonished Man.

Blaise Cendrars personified this condition. His name, a nom de plume, is a play on the French for embers (braise) and ashes (cendres). Here was a figure with an inexhaustible curiosity, insatiable for experience and the knowledge derived from it: for him life and intellect were one, a mind receptive and open. Cendrars was a joyous heretic consumed in the crucible of a life lived uncensored and from those embers his writing rose like a phoenix.

Among the books burnt in Bebelplatz that night were those written by Bauhaus members. When the Bauhaus closed in 1933 the intellectual and artistic diaspora carried its promethean program unbound.

Yet for every avantguard there is a counter movement that seeks to perpetuate regressive values, one that denounces fresh insight as fake: a verbal book burning.

In the case of Germany in 1933 the pyre called forth a fearful Tyger from the forests of the night. Cendrars’ library was destroyed by the Gestapo during the occupation of France.

Burnt book with crushed Amazonian charcoal.

295 x 250 x 30mm.

2022.

Available

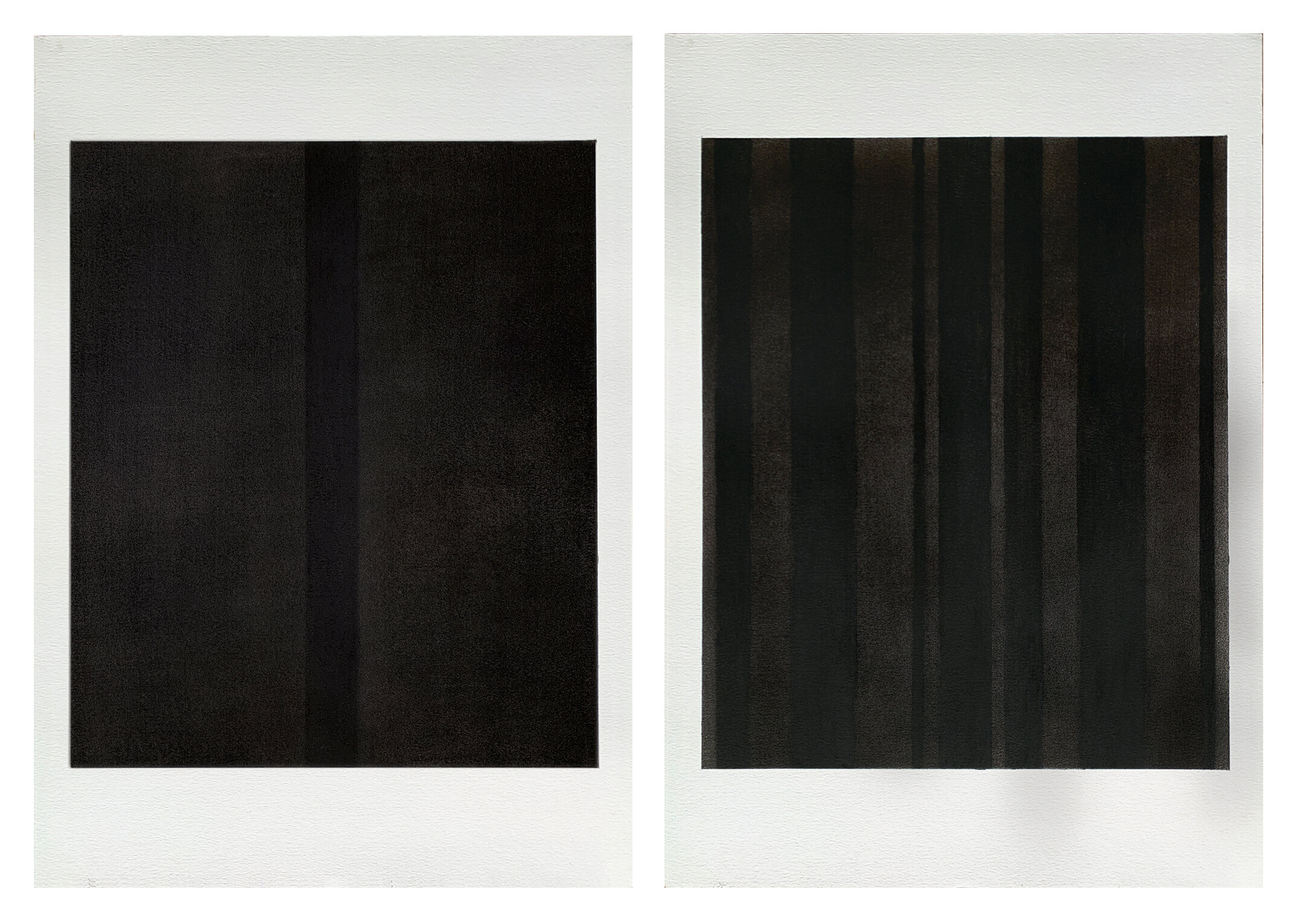

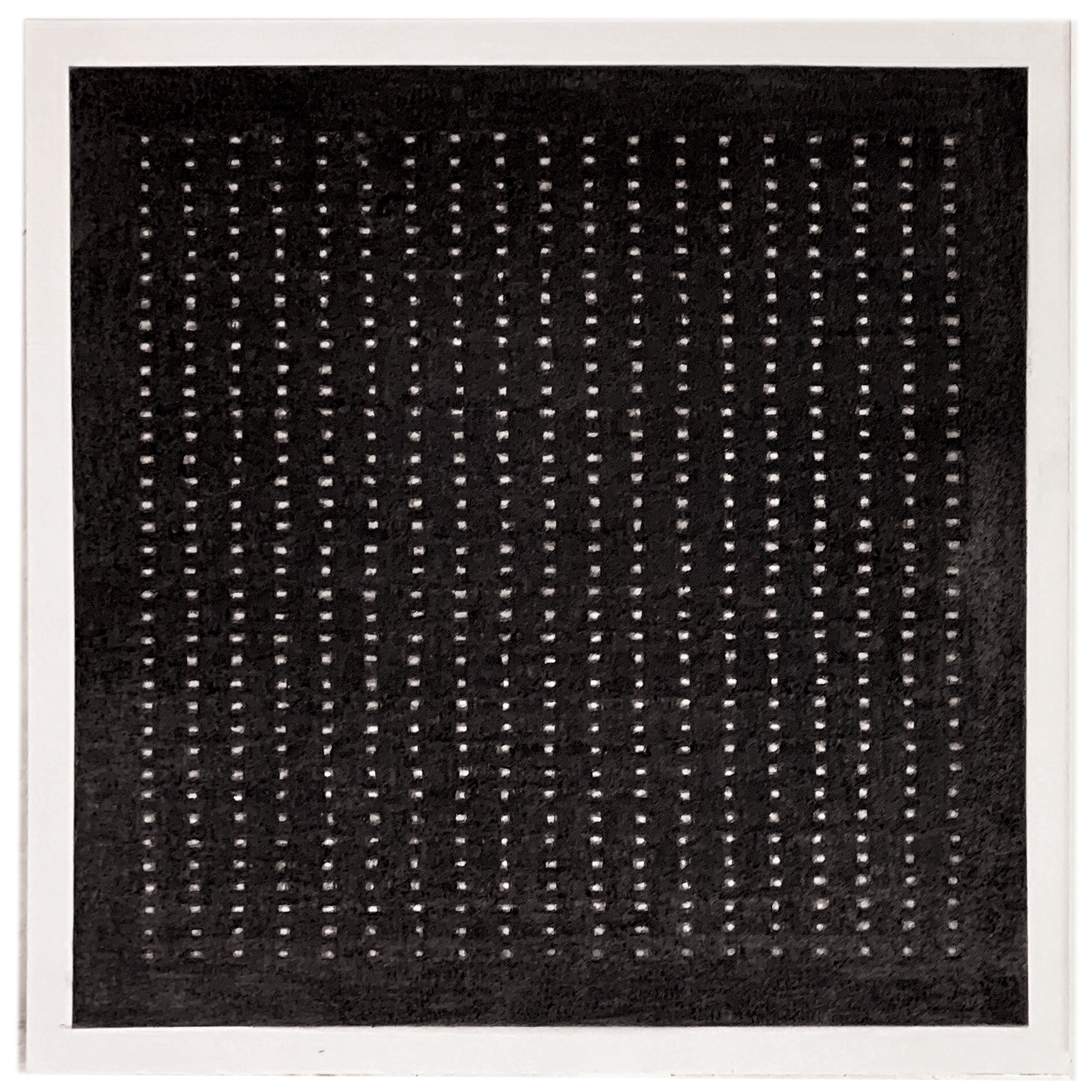

Right panel after ‘Abraham’ 1949: ‘Canto MMXX (2020)’.

Left panel after ‘Canto IV’ 1963.

Newman’s ‘Abraham’ of 1949 is the first post WWII Black Painting.

Here I have recreated Canto IV and then extended its ‘zero of form’ in the right panel. Rather than an I or 1 - which the central stripe could be read as representing the right panel has multiple verticals. These are in fact the Barcode for 2020 - this then is the Canto MMXX.

Newman’s selection of vertical divisions relate and define the body (and thus viewer) in space in relation to the painted surface.

Canto MMXX in this sense is not only a marking of time but an abstract expression of our present incarceration. We wish to roam unfettered once again, and we may yet, but our view of the near future is obscure.

Amazonian and Californian forest fire derived charcoal on paper.

Each panel 50 x 35cm.

2022.

Available

‘Homage to the Black Square’

When the Bauhaus finally closed Josef and Anni Albers emigrated from Berlin to the USA in 1933 and began teaching at Black Mountain College moving on to Yale in 1950.

Around the same time and at the age of 62 he began what would become the work for which he is now most widely recognized: The Homage to the Square series.

When he began this series of what would become over the course of the rest of his life experiments in the cosmos of colours and tonality he did so simply with black, white and mid-grey.

Even within these minimal means he achieved the maximum effect: the mid-gret appears not to be grey at all but a deep blue green. Even with a starkly hard edged composition the unexpected could happen.

And something very unexpected happen when I began to plot out my homage to the homage to the square: Albers first completed version has the exact dimensions as Kasimir Malevich’s first Black Square of 1915: 79.3 x 79.3.

This cannot be by accident since Russian, American and German systems of measurements are not the same. What this suggests is that Albers based at least his first square on that of Malevich. My version is an homage tripled.

To honour the subject was for Albars central to his meticulous practice and his subject was colour.

For my part in honouring both the subject and material I have used charcoal derived from forest/wild fires on three continents. Each charcoal has it’s own tonal qualities: Malibu is the lightest, Amazonian darker and ruddier and that from Andalucia almost black with a bluish tone.

Minimal means for maximum effect.

Three types of forest fire charcoal on paper.

79.5 x 79.5 cm

2022.

Available

‘She is Black’

Rauschenberg, like Baudelaire’s flaneur strolled through a ‘forest of symbols’ finding correspondences with which to create his own pictorial grammar. R found those connections by unfettered experimentation where inquisitiveness and intuition gave rise to a Bricoleur’s ‘combinatorial logic’, a ‘vision of the sensible world in which all things are interconnected’. R studied under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College and it is here that education itself underwent an experiment in bricolage aimed at just such a combinatorial logic with Art at its center.

R is perhaps the epitome of that project at BMC in which Art is the locus in which Observation, Judgement and Action are all at play and where there is no separation between art and life.

But perhaps liberty requires a reckoning and the period bookended by the end of WWII and 1968 was one in which both Existentialism and Abstract Expressionism occur concurrently. “In the middle of the journey of our life I came to myself within a dark wood where the straight way was lost. Ah, how hard a thing it is to tell what a wild, and rough, and stubborn wood this was, which in my thought renews the fear!” The many black paintings of this period suggest that after the inferno of WWII a transformation happened in the culture; a dark wood through which it was necessary to pass to reach sunlit uplands. At BMC there was attempt to find this new way via an oblique route.

Earlier in this series I reproduced images from Allais’ ‘April Foolish Album’ of 1887 in which there was both a black square and a silent score. R’s Untitled (Glossy Black Painting) and John Cage’s ‘4:33’ reify these tropes; a zero point from which the nascent new culture could spring. ‘Glossy Black Painting’ was made from the processed material world: in R’s case newspaper and sump oil. In ‘She is Black’ I have used forest fire derived charcoal and medium. In both the viewer is reflected, refracted: disassembled within the work itself.

Amazonian charcoal / medium on canvas.

45 x 45 cm.

2022

Available

‘The Firefly Cage’

Stella and Martin were both engaged in finding a structural and grammatical form of pictorial communication beyond a semiotic or representational language: one that is similar to the effect of music within the body rather than external to it; the eyes receive and participate in a visual evocation in a similar way to that of the ear’s reception of sound.

These images are programmatic yet are simultaneously random and contingent: human fallibility is inherent in their execution, the hand cannot but leave the trace of its presence: ‘There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in’. One begins to understand how these images work in the making of them: ‘learning by doing’. For the viewer there is also a reciprocity; the visual transmission is altered by the reception of it which in turn alters the perception of the image: it is an experience related to Bergson’s theory of time. The focus or attention over a period of time qualifies our perception of duration. In each we become absorbed and are lost.

The period in which these works were made was one characterized by a search for fresh insight and meaning. Art was the one such conduit for this and Agnes Martin drew from Zen teachings; her work accepted and was absorbed within the chaotic void addressing it calmly. ‘Nature’s perfection lies in the absolute, blind freedom of units within it’

Yet order of some kind seems forever desired; why do we attempt to impose it? This speaks of a sense of discord within rather than without: By placing ourselves apart from nature while knowing ourselves to be fallible we internalize this sense of chaos and fail to acknowledge that since ‘nature doesn’t make mistakes’ it’s ok, there is harmony we just have to tune in.

I have paired a version of Stella’s ‘Morro Castle’ with an ‘Untitled’ Martin to draw attention to aspects of duality both within and between them: both are serious yet playful, both are the result of a rigorous, intentional and limited process, one still, the other active, one recedes the other advances: yet all in concordance.

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

Each 35 x 50 cm.

2022.

Collection of G Grandfils, Barcelona, Spain

‘The Firefly Cage’

Stella and Martin were both engaged in finding a structural and grammatical form of pictorial communication beyond a semiotic or representational language: one that is similar to the effect of music within the body rather than external to it; the eyes receive and participate in a visual evocation in a similar way to that of the ear’s reception of sound.

These images are programmatic yet are simultaneously random and contingent: human fallibility is inherent in their execution, the hand cannot but leave the trace of its presence: ‘There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in’. One begins to understand how these images work in the making of them: ‘learning by doing’. For the viewer there is also a reciprocity; the visual transmission is altered by the reception of it which in turn alters the perception of the image: it is an experience related to Bergson’s theory of time. The focus or attention over a period of time qualifies our perception of duration. In each we become absorbed and are lost.

The period in which these works were made was one characterized by a search for fresh insight and meaning. Art was the one such conduit for this and Agnes Martin drew from Zen teachings; her work accepted and was absorbed within the chaotic void addressing it calmly. ‘Nature’s perfection lies in the absolute, blind freedom of units within it’

Yet order of some kind seems forever desired; why do we attempt to impose it? This speaks of a sense of discord within rather than without: By placing ourselves apart from nature while knowing ourselves to be fallible we internalize this sense of chaos and fail to acknowledge that since ‘nature doesn’t make mistakes’ it’s ok, there is harmony we just have to tune in.

I have paired a version of Stella’s ‘Morro Castle’ with an ‘Untitled’ Martin to draw attention to aspects of duality both within and between them: both are serious yet playful, both are the result of a rigorous, intentional and limited process, one still, the other active, one recedes the other advances: yet all in concordance.

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

Each 35 x 50 cm.

2022.

Available

There is a heightened sense that we are living through ‘unreal’ times. This echoes T.S. Eliot’s remark that humankind cannot bear very much ‘reality’. And there is a concomitant sense of stasis, of being held beside time.

The resulting disorientation - spatial as well as temporal has caused many to contemplate the value of all aspects of life when all bets are off regarding what may constitute a future reality in comparison to the illusion of plenitude which preceded this period.

Reinhardt’s commitment to his Black Paintings from the mid ‘50s drew from his interest in both Asian and European mysticism and formed an enquiry as to ’how it might be possible to give hidden forces a kind of visible form, that was like the forces themselves; both present and not quite visible’. As a reader of Alan Watts, Reinhardt was familiar with his take on the coincidentia oppositorum / unity of opposites; e.g. that darkness and light are co-extant.

He was also aware of Watts reading of Dewey’s ‘Transactionalism’; esp re the ‘organism-environment’ in which one cannot separate an organism from its environment and vice versa: the subject (observer) and object (observed) are inseparable. Reinhardt’s aesthetic arrived at images that conjured what Walter Benjamin called the ‘aura’, that reaffirmed the lost kinship between subject and object: reunifying what habitual modes of perception differentiate.

This quality of ‘presence’ in Reinhardt’s Black Paintings derives from their being substantially insubstantial and this ungraspability reflects that sense that we are living in unreal times, of both being there and not being there, outside of time. ‘Underlying the Black Paintings is the idea of the void, the field in which action and non-action are one, and which holds in perfect equilibrium these apparent opposties’

Our disquiet in quiet times means that the void is once again present in all our lives. It need not be feared. Merely, it should be understood as ‘natural’ and ‘normal’ and we are all now existentialists seeking light in the dark.

Three types of forest fire charcoal on paper.

90 x 90cm

2022.

Available

This series grew out of a larger project called Canopy. That project has been growing in scope over the last three years since I first began using forest fire derived charcoal as a drawing material. The simple aim for Canopy is help restore and protect forests effected by fire by making and selling artworks which are made from the charcoal from those places: to fight fire with fire.

The History of the Black Square came about since I was searching for simple, universal and repeatable motif for Canopy – one that didn’t take, as The Tainted Sublime series did, over a month to execute each piece.

From Robert Fludd to Mark Rothko I have traced this history while Covid19 has spread like, yes, a wildfire, globally. It has felt an entirely appropriate body of work to make.

It is true that ‘there is no such thing as a good painting about nothing’. Rothko also said he ‘began to use pure black as a colour of light not as a colour of darkness’ and indeed neither Rothko nor I suffer from chromophobia.

What Rothko sought, above all, was to speak of the tragedy of the human condition and to create with his work a kind of stage within which this drama can be encountered; the viewer an active participant. ‘Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?’ Gauguin’s famous, eternal and tripartite question could equally be the title of any of Rothko’s late works but especially that of the South Panel in the Menil Chapel. This panel has the same dimensions as Rodin’s ‘Gates of Hell’. Rodin’s source is Ghiberti’s ‘Gates of Paradise’ and both derive from Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Rothko’s South Panel offers no answer to Gauguin’s title, no illumination because really there is no knowable answer, no certainty, only the void from when we came and to which we will return.

However, I wanted to offer at least a glimmer of light and so the history of the black square as it draws near to a close is with a black square framing a hint of perhaps better times that may lie beyond these tragi-comic times. While there are further black squares after Rothko there is a finality to his Menil Chapel works. In my last piece there is also an inversion of the Robert Fludd image with which I began this series.

Charcoal and pigment on paper.

150x100cm.

2022.

Available

The progenitor of all subsequent black squares appears in Fludd’s Utriusque Cosmi Maioris Scilicet et Minoris Metaphysica, Physica Atque Technica Historia (Macrocosm Microcosm) published by Oppenheim (1617). Three versions all based on how it appears in the first edition of 1617 to match the original page and square dimensions:

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

300 x 200mm and 138 x 138mm.

2022.

Available

Referencing the minor tradition of ‘mourning pages’ in certain elegiac texts Sterne included a black page in the first volume of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759) in which Parson Yorick – a fictionalised self portrait of the author – dies.

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

Two versions matching the first edition of 1759: Octavo (228 x 152mm)

2022.

Available

In tracing the historical appearance of ‘The Black Square’ and in attempting to record its occurrence in chronological order I have had to retrace my steps, occasionally coming across an important instance in the chain.

Prior to its use by Laurence Sterne in Tristram Shandy it was used elegiacally. Sterne set a precedent in which it came to be used as a satirical, humorous or absurdist device.

Throughout the 19thC in France there is a sequence of such instances beginning with Cham’s ‘Histoire de Monsieur Lajaunisse’, 1839. The two panels here have the following captions: ‘L, having extinguished his candle returns to his bed in complete darkness’ ‘L can’t understand it. He has no pillows or covers and his mattress is as hard as a bench’

As we shall see this tradition continues up to and including Malevich’s now notorious hidden text in ‘Black Square on a White Round’ of 1915.

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

250 x 160mm.

2022.

Available

Diptych

Left Panel; After Pelez: ‘Effet de nuit qui n’est pas Claire de lune’, La Charivari, 19th March 1843

Right Panel; After Bertall: ‘Vue de La Hogue (effet de nuit) ((Jean-Louis Petit)), La Salon de 1843, August 1843.

The blank or rather black panel as a satirical device appears twice in 1843. Both times it is used comment upon what were simply dark paintings.

Nocturne as a term for and later a genre in painting occurs later in the nineteenth century. These two caricatures of actual paintings exhibited at the Salon of 1843 pass comment on paintings that were considered incomprehensible.

Pelez’s illustration in La Charivari on the ‘initial impressions of La Salon’ and later that year Bertall’s illustrated volume; a complete satirical revue of the salon further the visual convention and meaning of the black square .

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

Page/Panel size: Each 36x26cm

2022.

Available

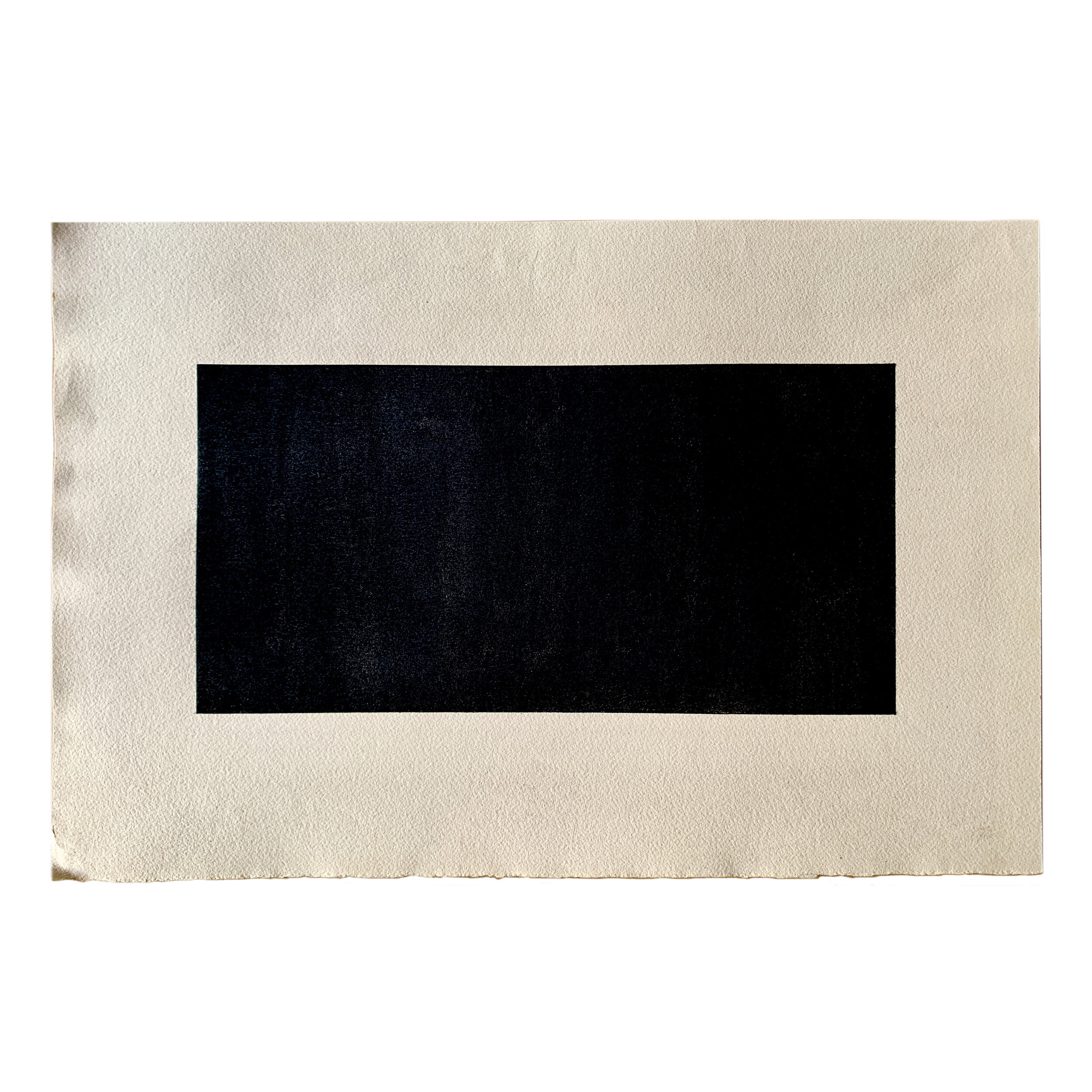

From ‘Histoire pittoresque, dramatique et caricaturale de la Sainte Russie d’apres les chroniqueurs et historiens Nestor, Nikan, Sylvestre, Karamsin, Segur, etc’ Paris, 1854.

Doré’s History of Holy Russia begins with a void, a black square and one can draw the analogy that Malevich’s ‘Black Square on a White Ground’ thus marks the end of that history; that it begins and ends with the ineffable: in the void.

Doré’s History is comprised of 500 loosely sequential images and was intended as both satire and anti-Russian propaganda during the Crimean War in which France and Russia were adversaries.

As such , the opening image of a black square is a very pointed ‘black mark’ against Russia.

As with all of these early instances I have reproduced the black square as it appears upon the page of the original publication.

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

Page size: 298 x 203mm.

2022.

Available

Bilhaud exhibited his dubiously titled all black painting in the Salon des Incohérents in 1882. It is the first fully monochrome or ‘monochroidal’ painting.

While the painting appears to be lost we know of its existence since it is directly referenced in the next instance in this sequence by Alphonse Allias.

If Combat de Négres, created by a humourist, was merely an absurdist joke (and one which as demonstrated in this series has a clear lineage) then it is remarkable that it did not wear thin sooner.

Again, the black square appears at a pivotal moment in history. In 1882, in his critique of the Enlightenment; ‘The Gay Science’, Friedrich Nietzsche declares the God is dead. In this context and, again, reaching its apogee in Malevich’s Black Square becomes significant of an age of ‘endarkenment’. I have inscribed beneath the charcoal my own, more apt title, a quote from Robert Pogue Harrison’s ‘Forests – The Shadow of Civilization’: ‘For all its glory, civilization cannot console us for the loss of what it destroys’

To arrive at appropriate dimensions for this piece I have referenced Alphonse Allias reproduction. It is thus a picture of a picture of a picture.

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper.

360 x 170mm.

2022.

Available

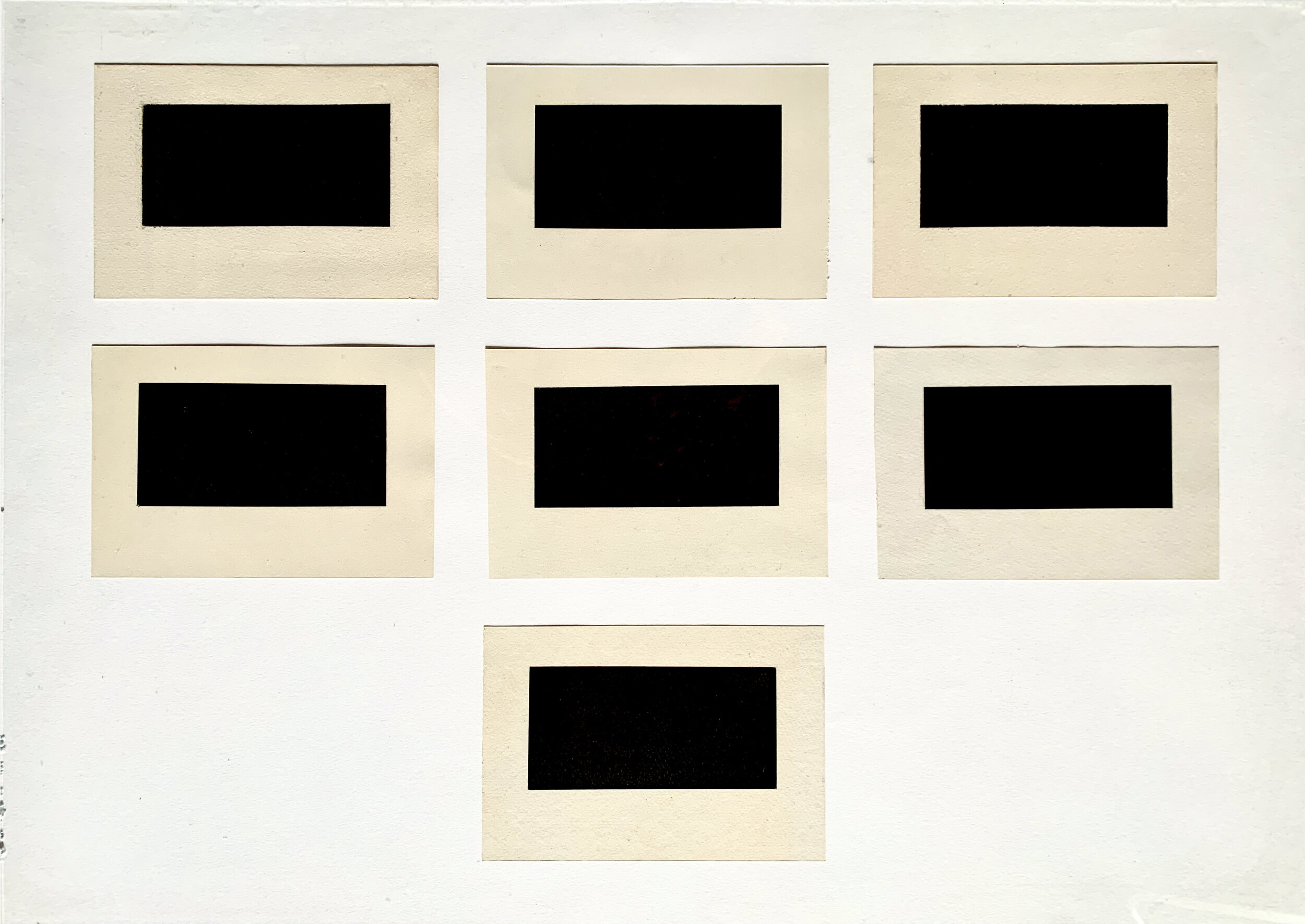

The inscription under Malevich’s Black Square on a White Ground, discovered in 2015: "Battle of negroes in a dark cave" appears to directly reference the caption to accompany the black monochrome in Allais’ absurdist ‘April Foolish Album’; “Combat de Nègres dans une cave pendant la nuit”

The Album is a monograph consisting of seven differently coloured monochrome plates and a score for a silent funeral march.

The seven captions can be found here :

https://www.wikiart.org/en/alphonse-allais/all-works#!#filterName:all-paintings-chronologically,resultType:masonry

Allais’ black plate in this volume directly references the previous instance in the sequence of black squares. Allais’ version is the only known illustration of Bilhaud’s black canvas. To arrive at the size and proportions of my recreation of Bilhaud’s image I added the sum of the areas of Allais’ seven coloured monochromes, while also rendering each black; thereby arriving at an equalization of both form and content.

Read in this, the original context, Malevich’s quotation of Allais’ caption for the colour black is less abhorrent than at first it appears. It is at odds with Malevich’s stated unitarian intentions for, and inspiration behind his arrival at The Black Square. However a retrospective reading of it that takes the quote into account does not truly reflect those intentions since at no stage does he reveal, title or write about this hidden inscription. What it does reveal is that Malevich’s Black Square is deadly serious but not necessarily somber - it carries and transmits the absurdity of life in a forest of symbols.

The hidden inscription and title for this heptatych derives from Plato’s Allegory of the Cave from The Republic: VII 517 a) in which a willed ignorance seems to triumph over elucidation. ‘In total darkness all things are equal’

Seven panels, each 124x185mm.

Amazonian charcoal on antique paper, 2022.

Available

‘Whereof One Cannot Speak, Therof One Must Be Silent’

Wittgenstein’s aphorism (from Tractatus Logic-Philosophicus) along with Einstein’s aphoristic equation and Rutherford’s splitting of the atom all arrive during a short span of human history, in the blink of an eye.

Nature, now firmly in humanity’s facile grasp, is being prised open to reveal its innermost secrets: The übermensch has arrived and the will to power - at the expense of millions of lives– scourges the earth.

Malevich’s move towards his own ‘zero of form’ has its inception in his designs for the Russian Futurist opera “Victory over the Sun’ of 1913.

With his first ‘Black Square’ Malevich arrives at, as Tatiana Tolstaya has described it: ‘that critical, mysterious, coveted point after which, because of which and beyond which nothing exists and nothing can exist’. It is simultaneously a summation, conjoinment, apogee and a negation of all icons, all referential and reverential visual forms of communication. But it is not mute: it addresses directly, defiantly the ever receding and insubstantial void from which we came and to which we shall return.

It is both a curse and a liberation, and as we shall see we must be careful not to be burnt by the sun as we capture it.

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

79.5 x 79.5 cm

2022.

Available

‘Madmen who ceaselessly complain of nature, learn that all your evils arise from yourselves’ (JJ Rousseau)

The second version of Malevich’s Black Square was painted in 1923 and made to be exhibited at the Venice Biennale the following year.

The Black Square of 1923 was shipped to Venice with ‘Black Circle’ and ‘Black Cross’ and appeared in the catalogue but it seems they were never shown: Various sources attest to this and what is clear from these is that Malevich’s Suprematist work was not regarded as representative of Soviet art by the officials in charge of the Russian pavilion.

By this time Malevich was the principal of the State Institute of Artistic Culture in Petrograd (St Petersburg) and although previously an active member of the revolutionary art committees by 1923/4, and with the death of Lenin, the shift towards an official Socialist Realism under Stalin had begun.

The 1923 Black Square is the largest of the four versions Malevich painted.

My intention was to complete and exhibit all the works of this series together. That might still happen (since I can replicate works) but in the current situation these are all for sale. If interested in this or any other of the series send me a PM to enquire

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

106 x 106 cm.

2022.

“The Sublime Void’

A total eclipse ... and then came the ice of Stalinism crushing the cultural avant-garde: The ‘Victory Over the Sun’ desired by the Russian Futurists, this revolutionary tearing of the veil of the old order summoned the void; something inchoate, inexpressible and beyond reason: Zaum.

If ‘the painters task is to discover things not seen … presenting to plain sight what does not actually exist’ then painting could unite lowly manual labour with lofty mental conception and span the gap between the visible world and the immaterial realm.

As Hans Belting describes it there is an historical shift between intra-mission and extra-mission: between what we receive through perception and what we project through imagination, or belief. Malevich asks us to ‘swim into the abyss’ to exist between the two states. That the Black Square; such an absolute, concrete image should become the significant of this is no accident: it is the emblem of the certainty of uncertainty - both of the void and a barrier and it is up to us to discern which it represents for us and us alone.

Thus Joseph Conrad’s dictum: ‘the discovery of new values in life is a very chaotic experience: there is …a momentary darkness’ and to paraphrase James Lovelock ‘no one can second guess the future’. These are the reasons why many feel the Black Square to be frightening.

By 1929 the Black Square has begun to multiply and replicate itself: It is as if it constitutes the new tabula rasa and the primary locus within which painting can now truly, honestly begin to address the absurdity of life.

Tatyana Tolstaya suggests that for all artists there is a’ pre-square’ phase but once they have stared unflinching into this void they become ‘post-square’ : that is to say truly an artist, at home in what Gaston Bachelard terms an intimate immensity.

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

79.5 x 79.5cm.

2022.

‘A Quintessence even from Nothingness’

John Donne

In late 1930 Malevich was arrested and imprisoned as Stalinism became ever more proscriptive of progressive art, ever more prescriptive in favour of Socialist Realism.

The arrest was, in part, due to his taking part in the 1927 Große Berliner Kunstausstellung. Hoping to return to Germany he left 73 paintings with Hugo Häring.

Those paintings were, over the years, dispersed and served to disseminate Malevich’s ouvre, reputation and influence, particularly via a major exhibition at MoMA in New York in 1936. This show lead directly to the formation of the American Abstract Artists Group.

The Black Square was Malevich’s emblem; an entirely modern Ikon and one that provided ‘an image for the longing that pervades human finitude’. This last version, a defiant rebuke, is his memorial, epitaph and testament. When he died in 1935 it was hung above his coffin, on the front of the funeral procession and mourners carried a banner with a Black Square. His tombstone (now lost), below an old oak tree in Nemchinokova was a stone cube with a Black Square.

Next we will move chronologically beyond the Malevich’s Black Squares: Art goes on generating art, every critical response is a rebirth or renascence - revivifying the work that prompted it. Evidently this is the case with Malevich’s Black Squares; both literally and figuratively this symbolic ‘quintessence even from nothingness’ has reverberated down the years to our own epochal moment.

It is precisely in this, our own global period of darkness that new values must be found and while ‘The discovery of new values in life is a very chaotic experience, there is a momentary feeling of darkness’ … upon our emergence from it ‘we may be as close to a better world as we will ever come’ and we will require an equally potent banner.

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

53.5 x 53.5cm.

2022.

Available

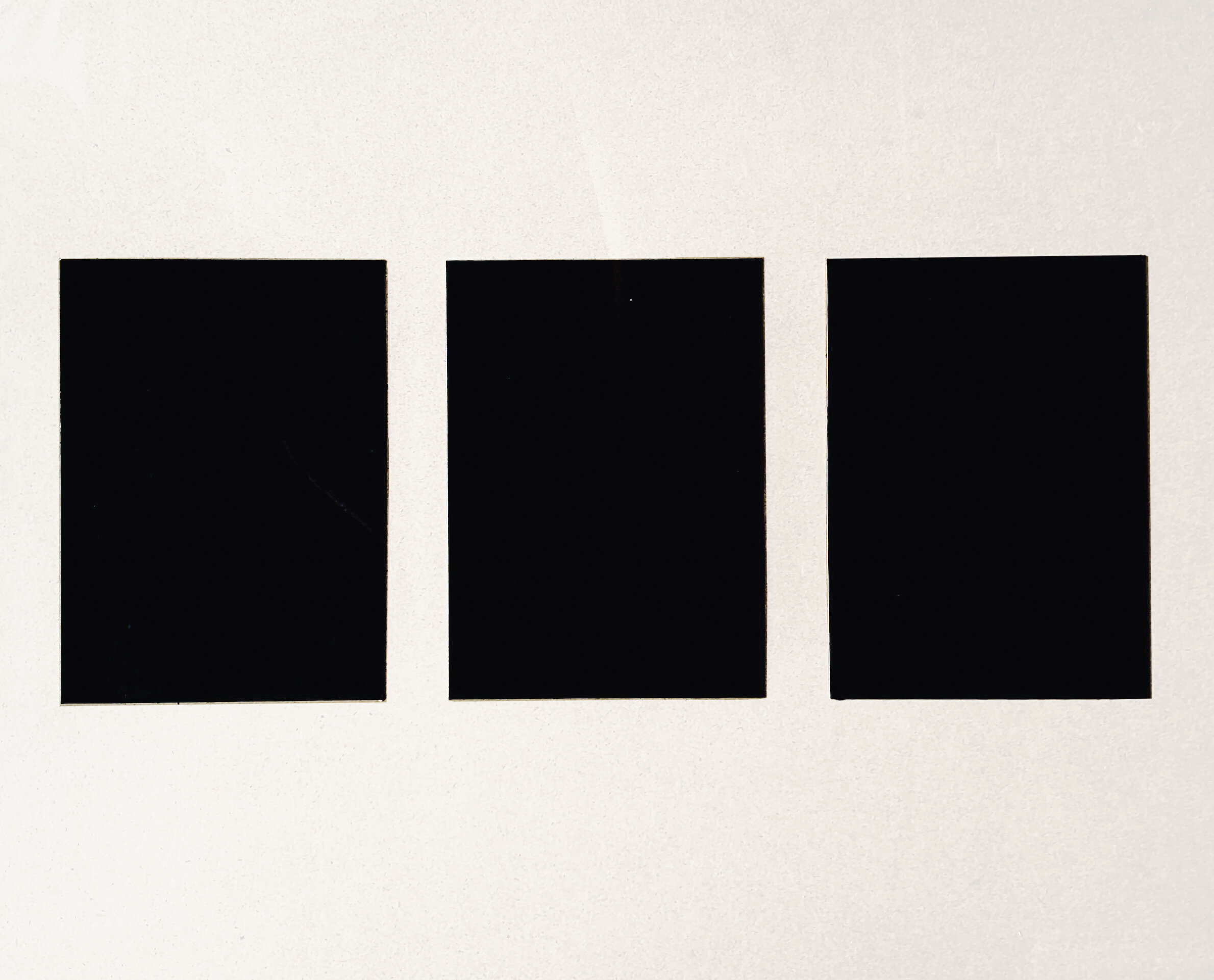

Between the dark void from whence we came and to which we will all return - Hegel called this condition ‘that undifferentiated night in which, as we say, all cows are black’ there is the world: the stage upon which we, if we are fortunate, through seven acts, play our roles: Life as mere ephemeral drama. What comes before and after is unknowable.

If life is but ‘sound and fury’ signifying nothing then the ‘nothing‘ that is, by it’s absence, defined is the disordered void: chaos.

However, without darkness there can be no light; darkness is the precondition of it. The silent, expectant darkness of the stage, the cinema or the screen is the necessary context in which life is framed and represented as drama; teleological being as opposed to meaningless nothingness.

As we sit in atomized confinement within our own personal Camera Obscuras, our screens become the apertures through which we watch the unfolding drama of Covid 19. Each night we take to our balconies and windows to applaud the principal actors in this absurd and surreal roman à clef while we look upon an empty stage; the city streets, squares and parks that were until recently our stage where we were the principal actors in our own lives.

In 1928 Man Ray Directed ‘L'Étoile de Mer’, written by surrealist poet and writer Robert Desnos. Man Ray gave Desnos a photo with the dedication written on the white mount: ‘To Robert Desnos, lots of things that absorb light’. This ‘rayograph’; executed in a dark room is a contradiction: the image would be white if was indeed an exposure of things that absorb light. Yet it alludes to the tradition of the matte in theatre and cinema: the structural device with which the acts and scenes of a play or film begin, are divided and ultimately fade to black.

Night falls, the sun also rises.

Three panels/acts:

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

Each 23.9 x 17.8 cm

2022.

Available

‘The Tyger and the Phoenix’

May 1933: Darkness descends as a crowd gathers in Bebelplatz in Berlin. Soon, eyes begin to glitter and shine with the fervour of zealots.

It is said that knowledge is power but what of the power of willed ignorance bought forth by the deliberate, symbolic destruction of knowledge?

The ritual of purification enacted by the burning of recorded knowledge has but one aim: to draw from those flames ‘mind forg’d manacles’: mental slavery, and the history of this rite is exactly coterminous with that of recorded knowledge.

Only by a forced adherence to an orthodox truth, it seems, can there be any power over knowledge. By extinguishing the light of knowledge those that burn books exemplify the notion that ‘there is no necessary equation between light and enlightenment or lucidity’: In fact what is instilled by this ceremony is the belief in a reduced and rectified scripture: orthodoxy.

Man is otherwise perpetually L'Homme Foudroyé: Astonished Man.

Blaise Cendrars personified this condition. His name, a nom de plume, is a play on the French for embers (braise) and ashes (cendres). Here was a figure with an inexhaustible curiosity, insatiable for experience and the knowledge derived from it: for him life and intellect were one, a mind receptive and open. Cendrars was a joyous heretic consumed in the crucible of a life lived uncensored and from those embers his writing rose like a phoenix.

Among the books burnt in Bebelplatz that night were those written by Bauhaus members. When the Bauhaus closed in 1933 the intellectual and artistic diaspora carried its promethean program unbound.

Yet for every avantguard there is a counter movement that seeks to perpetuate regressive values, one that denounces fresh insight as fake: a verbal book burning.

In the case of Germany in 1933 the pyre called forth a fearful Tyger from the forests of the night. Cendrars’ library was destroyed by the Gestapo during the occupation of France.

Burnt book with crushed Amazonian charcoal.

295 x 250 x 30mm.

2022.

Available

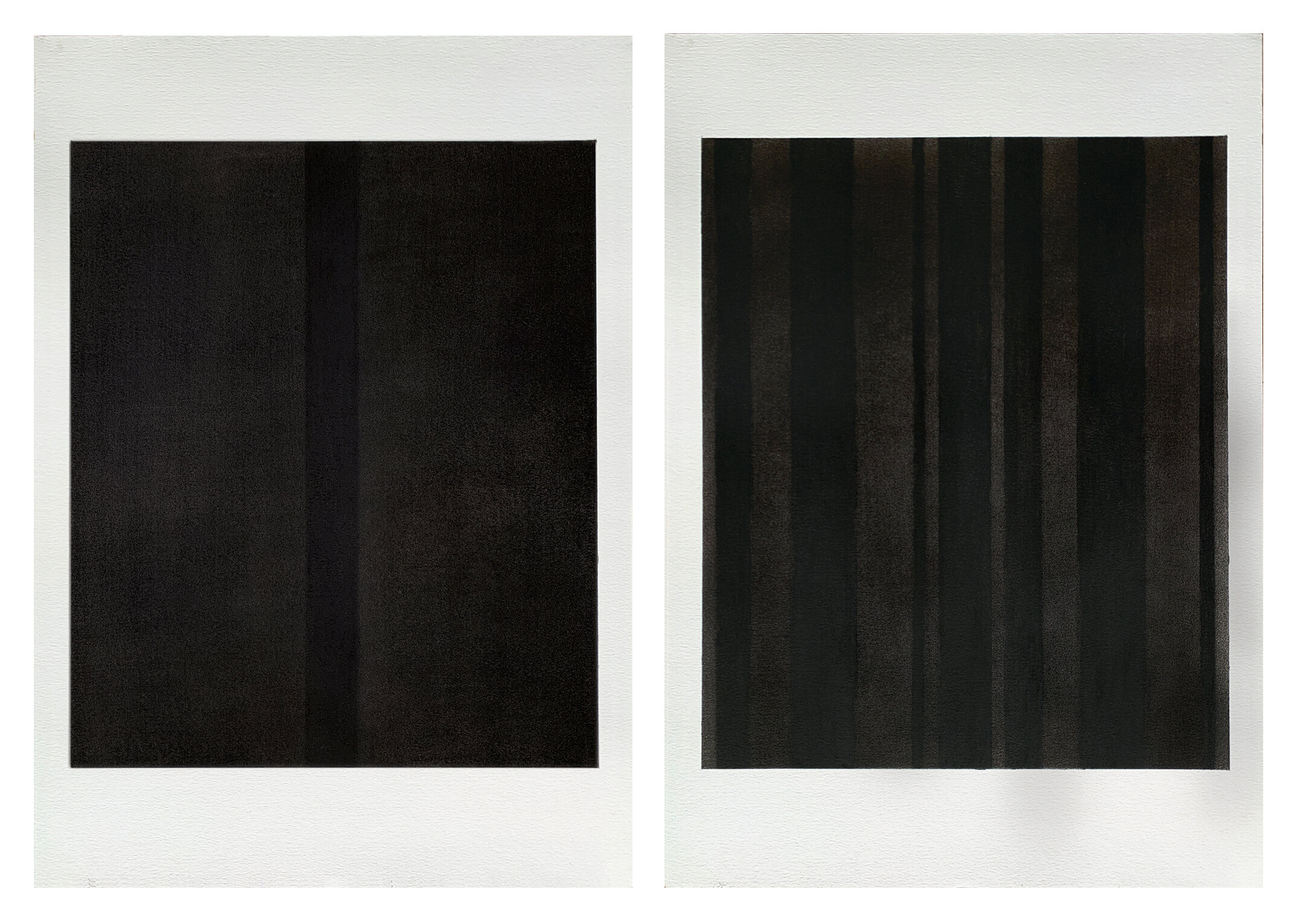

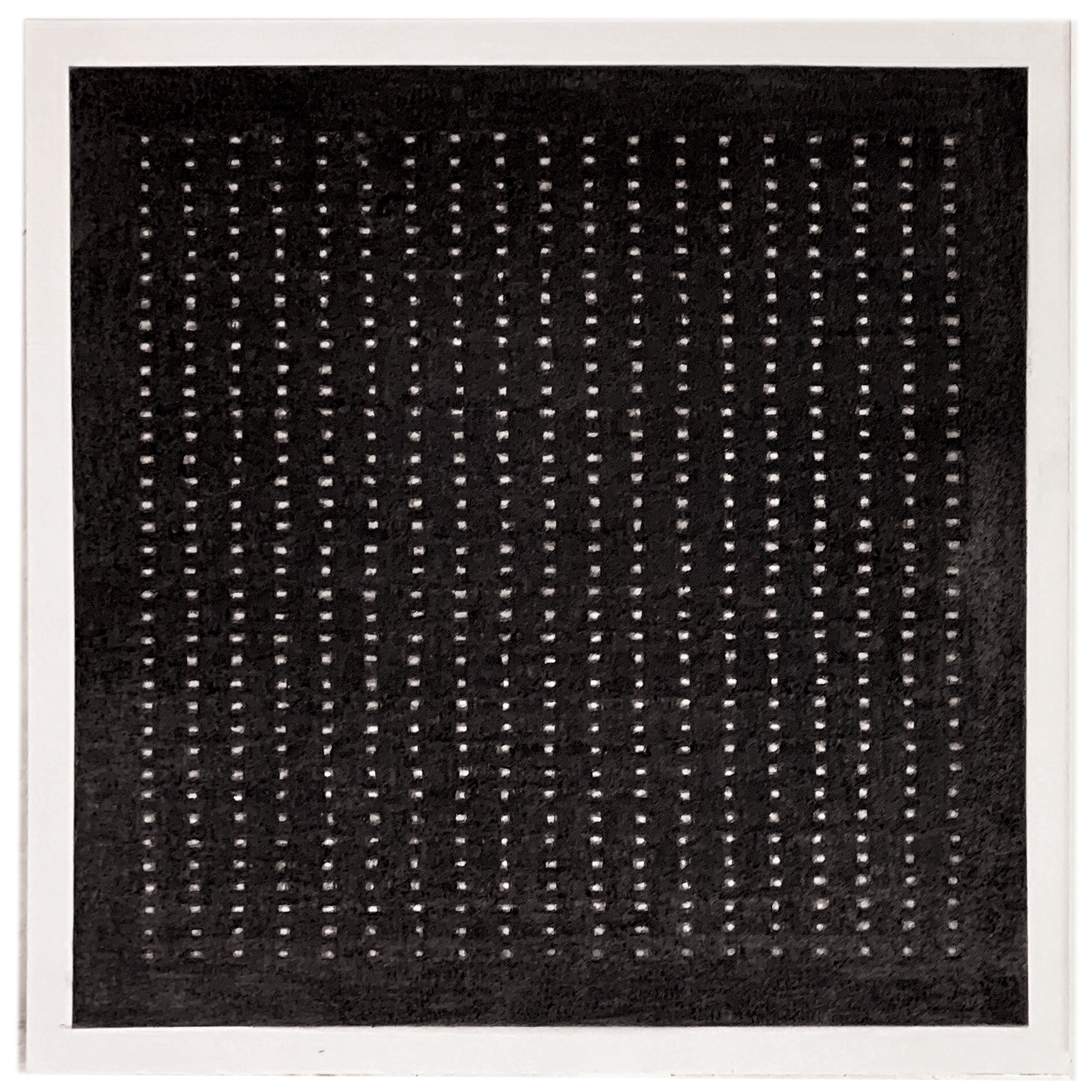

Right panel after ‘Abraham’ 1949: ‘Canto MMXX (2020)’.

Left panel after ‘Canto IV’ 1963.

Newman’s ‘Abraham’ of 1949 is the first post WWII Black Painting.

Here I have recreated Canto IV and then extended its ‘zero of form’ in the right panel. Rather than an I or 1 - which the central stripe could be read as representing the right panel has multiple verticals. These are in fact the Barcode for 2020 - this then is the Canto MMXX.

Newman’s selection of vertical divisions relate and define the body (and thus viewer) in space in relation to the painted surface.

Canto MMXX in this sense is not only a marking of time but an abstract expression of our present incarceration. We wish to roam unfettered once again, and we may yet, but our view of the near future is obscure.

Amazonian and Californian forest fire derived charcoal on paper.

Each panel 50 x 35cm.

2022.

Available

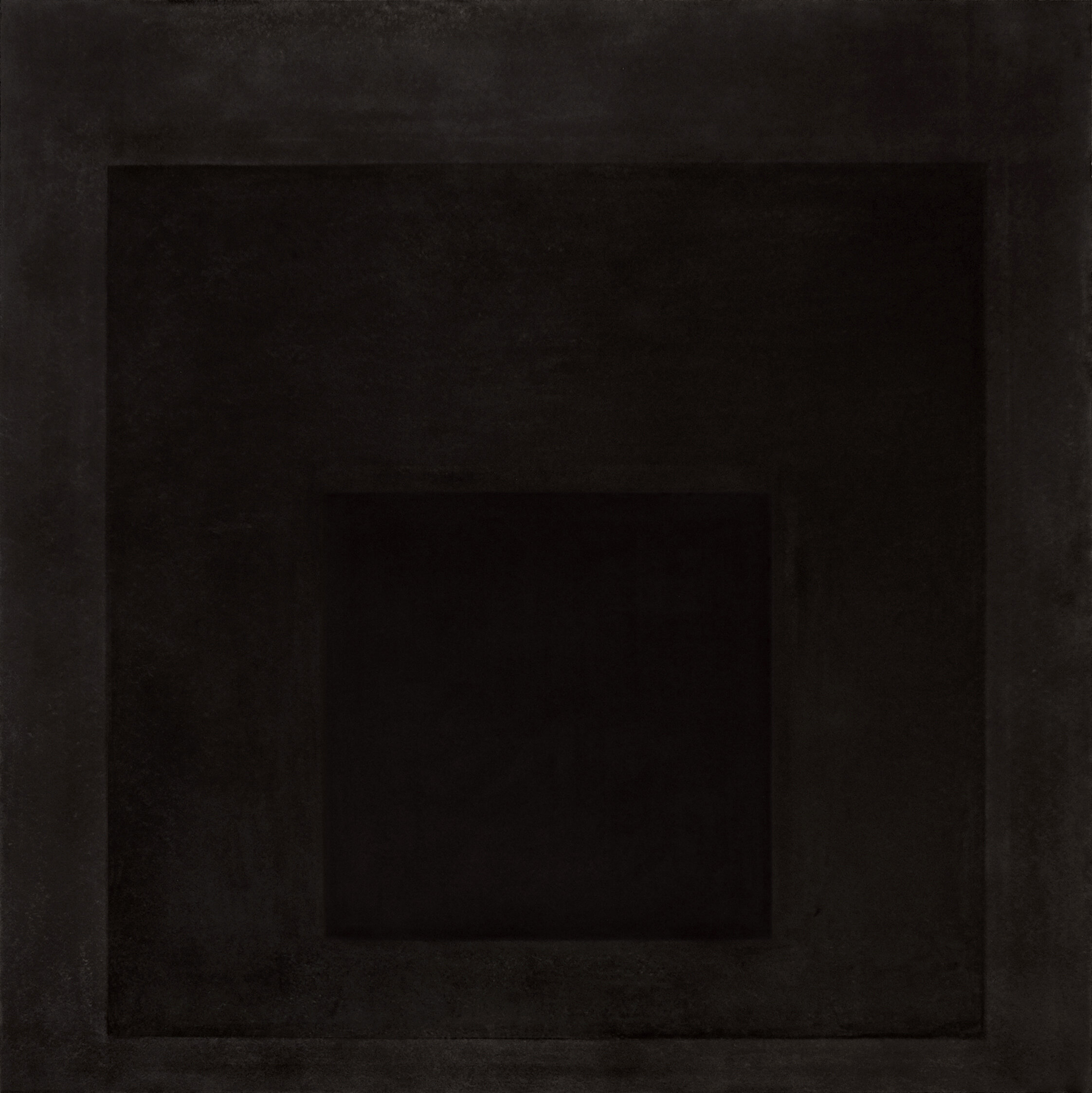

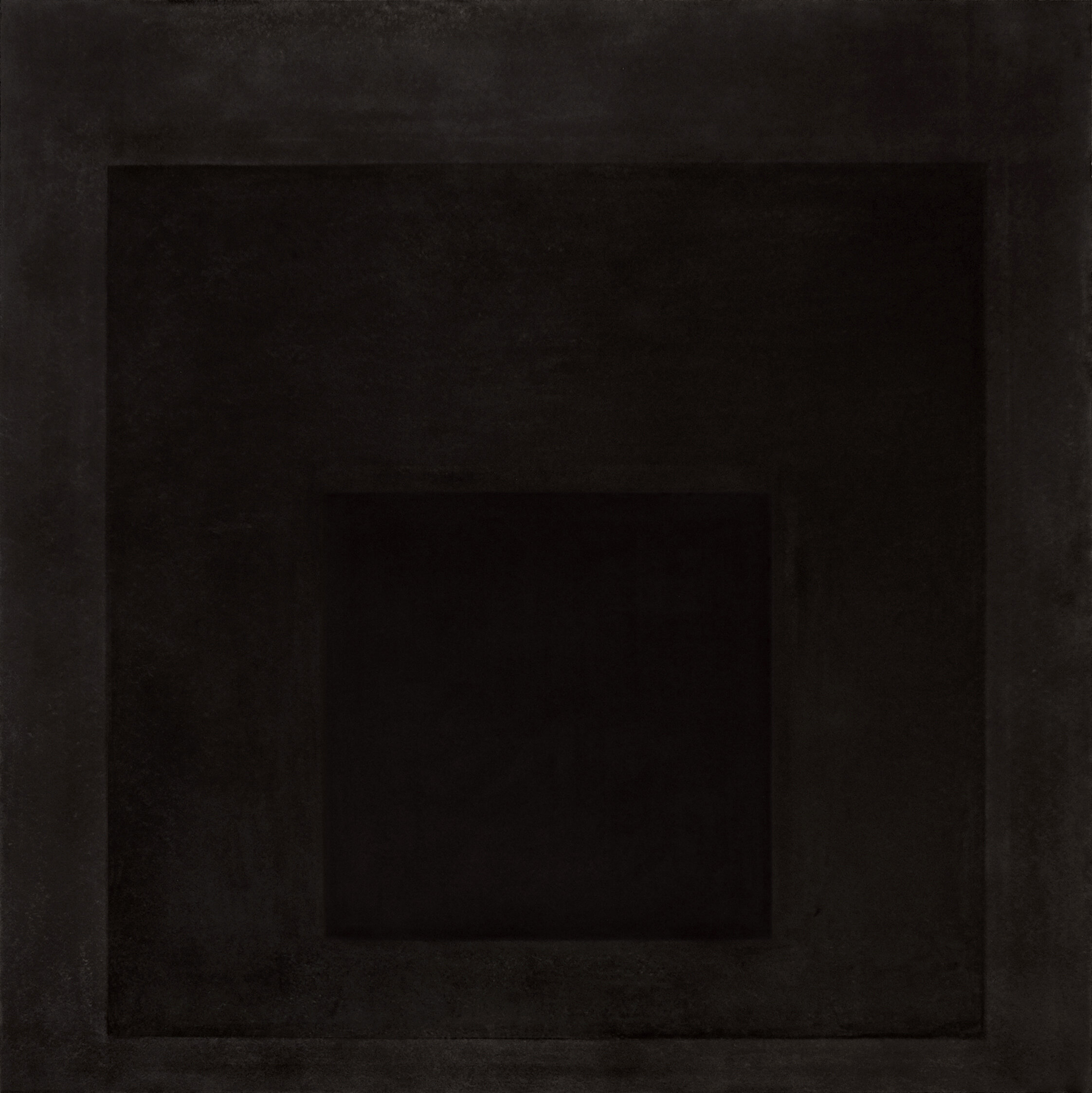

‘Homage to the Black Square’

When the Bauhaus finally closed Josef and Anni Albers emigrated from Berlin to the USA in 1933 and began teaching at Black Mountain College moving on to Yale in 1950.

Around the same time and at the age of 62 he began what would become the work for which he is now most widely recognized: The Homage to the Square series.

When he began this series of what would become over the course of the rest of his life experiments in the cosmos of colours and tonality he did so simply with black, white and mid-grey.

Even within these minimal means he achieved the maximum effect: the mid-gret appears not to be grey at all but a deep blue green. Even with a starkly hard edged composition the unexpected could happen.

And something very unexpected happen when I began to plot out my homage to the homage to the square: Albers first completed version has the exact dimensions as Kasimir Malevich’s first Black Square of 1915: 79.3 x 79.3.

This cannot be by accident since Russian, American and German systems of measurements are not the same. What this suggests is that Albers based at least his first square on that of Malevich. My version is an homage tripled.

To honour the subject was for Albars central to his meticulous practice and his subject was colour.

For my part in honouring both the subject and material I have used charcoal derived from forest/wild fires on three continents. Each charcoal has it’s own tonal qualities: Malibu is the lightest, Amazonian darker and ruddier and that from Andalucia almost black with a bluish tone.

Minimal means for maximum effect.

Three types of forest fire charcoal on paper.

79.5 x 79.5 cm

2022.

Available

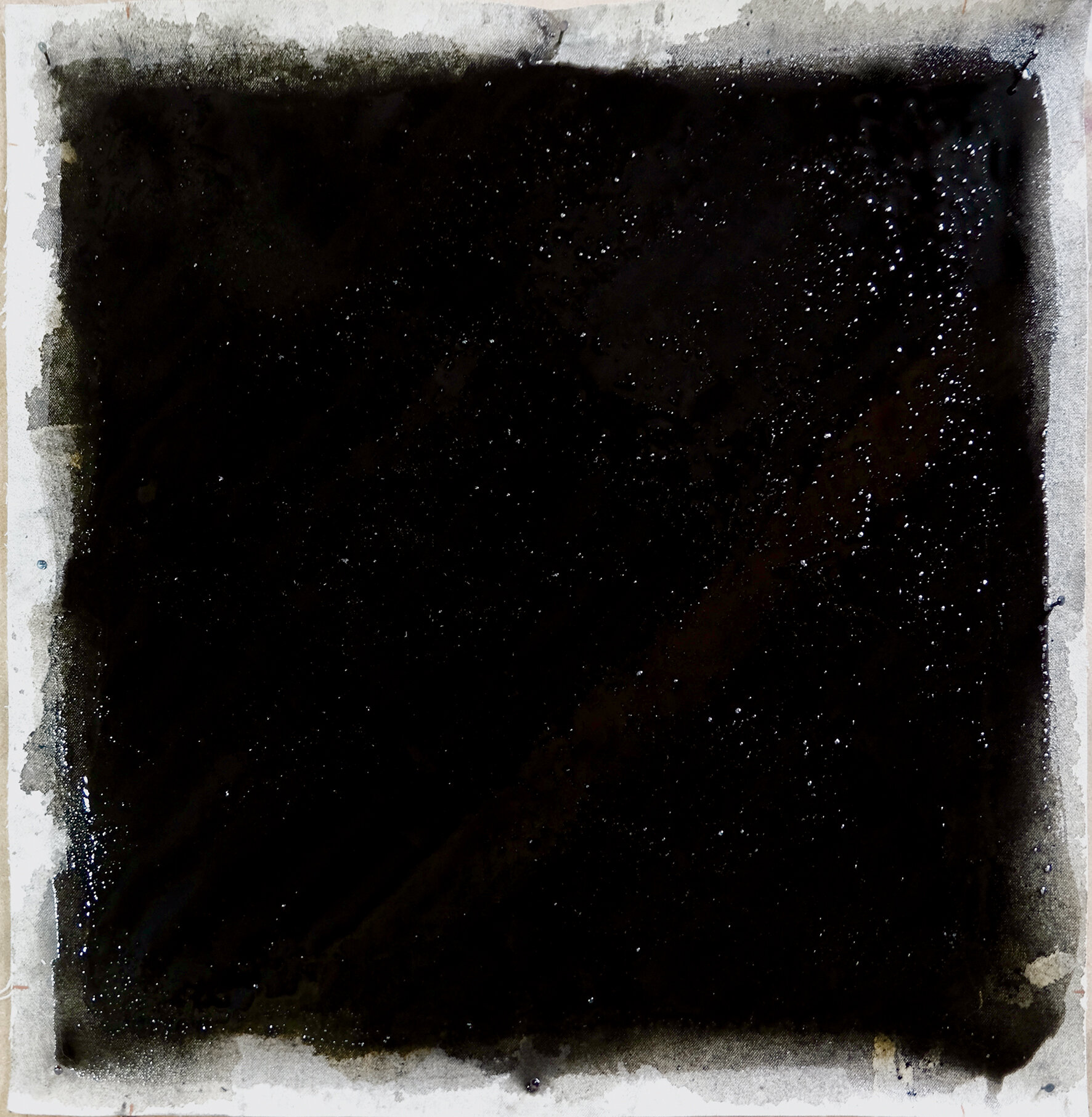

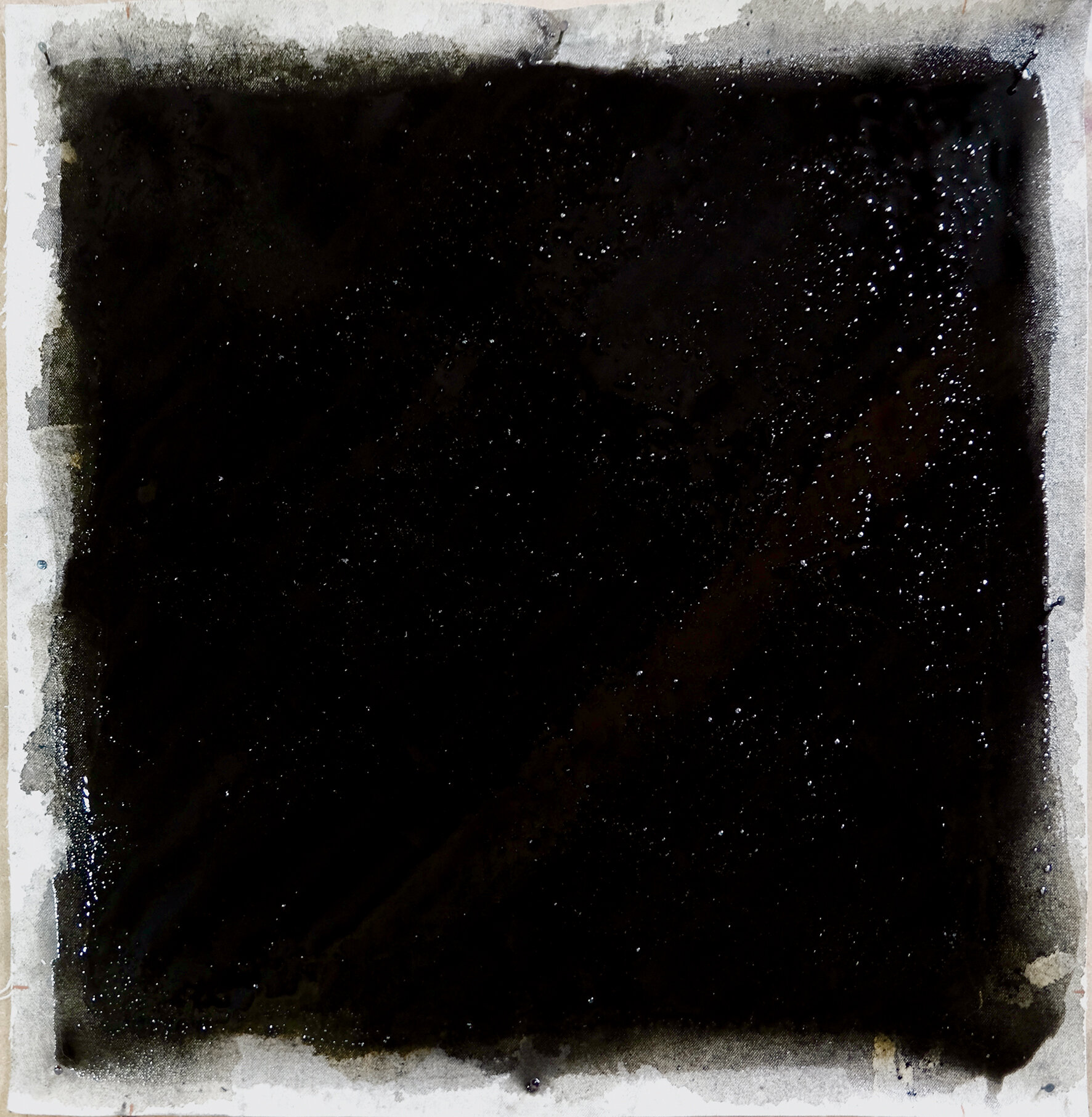

‘She is Black’

Rauschenberg, like Baudelaire’s flaneur strolled through a ‘forest of symbols’ finding correspondences with which to create his own pictorial grammar. R found those connections by unfettered experimentation where inquisitiveness and intuition gave rise to a Bricoleur’s ‘combinatorial logic’, a ‘vision of the sensible world in which all things are interconnected’. R studied under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College and it is here that education itself underwent an experiment in bricolage aimed at just such a combinatorial logic with Art at its center.

R is perhaps the epitome of that project at BMC in which Art is the locus in which Observation, Judgement and Action are all at play and where there is no separation between art and life.

But perhaps liberty requires a reckoning and the period bookended by the end of WWII and 1968 was one in which both Existentialism and Abstract Expressionism occur concurrently. “In the middle of the journey of our life I came to myself within a dark wood where the straight way was lost. Ah, how hard a thing it is to tell what a wild, and rough, and stubborn wood this was, which in my thought renews the fear!” The many black paintings of this period suggest that after the inferno of WWII a transformation happened in the culture; a dark wood through which it was necessary to pass to reach sunlit uplands. At BMC there was attempt to find this new way via an oblique route.

Earlier in this series I reproduced images from Allais’ ‘April Foolish Album’ of 1887 in which there was both a black square and a silent score. R’s Untitled (Glossy Black Painting) and John Cage’s ‘4:33’ reify these tropes; a zero point from which the nascent new culture could spring. ‘Glossy Black Painting’ was made from the processed material world: in R’s case newspaper and sump oil. In ‘She is Black’ I have used forest fire derived charcoal and medium. In both the viewer is reflected, refracted: disassembled within the work itself.

Amazonian charcoal / medium on canvas.

45 x 45 cm.

2022

Available

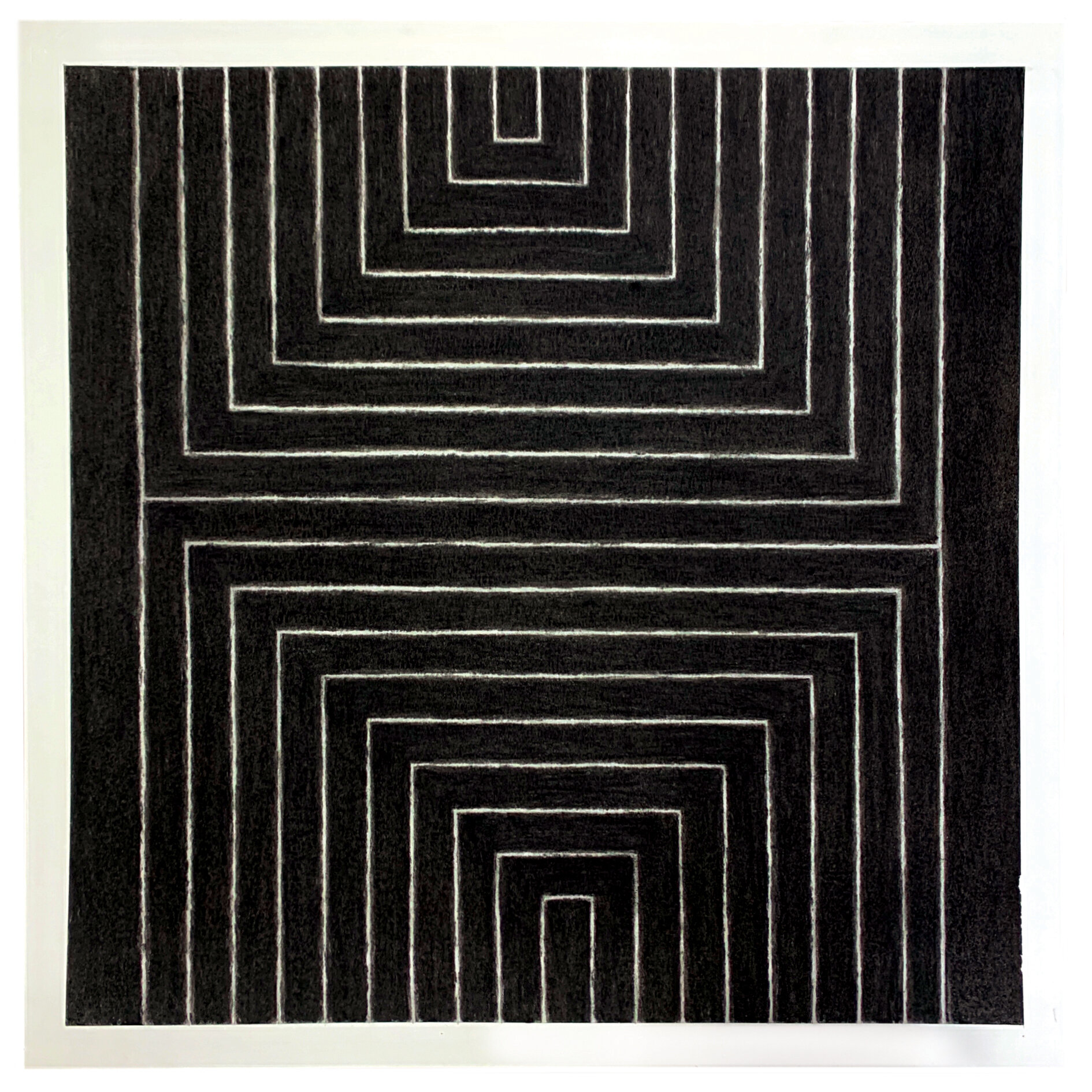

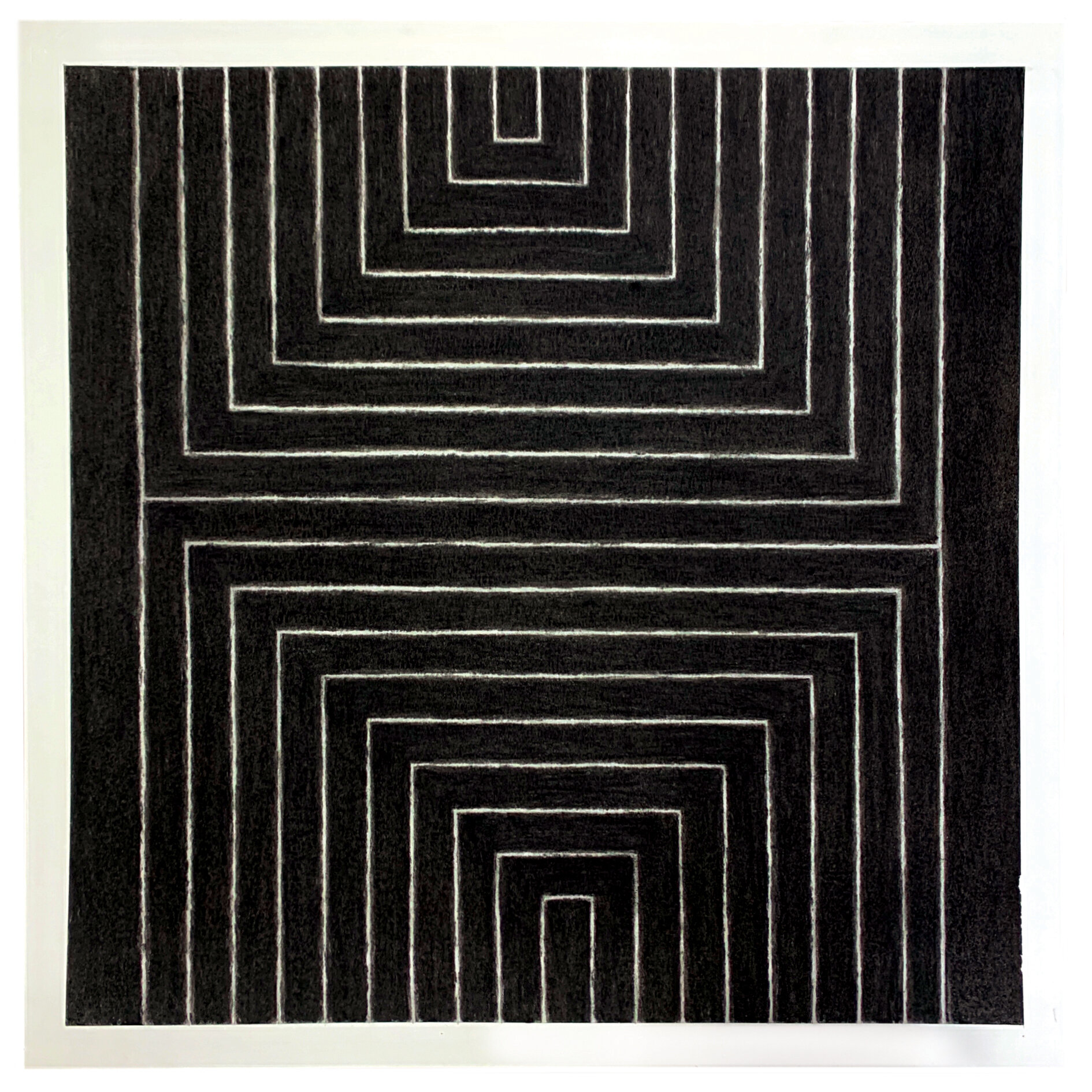

‘The Firefly Cage’

Stella and Martin were both engaged in finding a structural and grammatical form of pictorial communication beyond a semiotic or representational language: one that is similar to the effect of music within the body rather than external to it; the eyes receive and participate in a visual evocation in a similar way to that of the ear’s reception of sound.

These images are programmatic yet are simultaneously random and contingent: human fallibility is inherent in their execution, the hand cannot but leave the trace of its presence: ‘There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in’. One begins to understand how these images work in the making of them: ‘learning by doing’. For the viewer there is also a reciprocity; the visual transmission is altered by the reception of it which in turn alters the perception of the image: it is an experience related to Bergson’s theory of time. The focus or attention over a period of time qualifies our perception of duration. In each we become absorbed and are lost.

The period in which these works were made was one characterized by a search for fresh insight and meaning. Art was the one such conduit for this and Agnes Martin drew from Zen teachings; her work accepted and was absorbed within the chaotic void addressing it calmly. ‘Nature’s perfection lies in the absolute, blind freedom of units within it’

Yet order of some kind seems forever desired; why do we attempt to impose it? This speaks of a sense of discord within rather than without: By placing ourselves apart from nature while knowing ourselves to be fallible we internalize this sense of chaos and fail to acknowledge that since ‘nature doesn’t make mistakes’ it’s ok, there is harmony we just have to tune in.

I have paired a version of Stella’s ‘Morro Castle’ with an ‘Untitled’ Martin to draw attention to aspects of duality both within and between them: both are serious yet playful, both are the result of a rigorous, intentional and limited process, one still, the other active, one recedes the other advances: yet all in concordance.

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

Each 35 x 50 cm.

2022.

Collection of G Grandfils, Barcelona, Spain

‘The Firefly Cage’

Stella and Martin were both engaged in finding a structural and grammatical form of pictorial communication beyond a semiotic or representational language: one that is similar to the effect of music within the body rather than external to it; the eyes receive and participate in a visual evocation in a similar way to that of the ear’s reception of sound.

These images are programmatic yet are simultaneously random and contingent: human fallibility is inherent in their execution, the hand cannot but leave the trace of its presence: ‘There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in’. One begins to understand how these images work in the making of them: ‘learning by doing’. For the viewer there is also a reciprocity; the visual transmission is altered by the reception of it which in turn alters the perception of the image: it is an experience related to Bergson’s theory of time. The focus or attention over a period of time qualifies our perception of duration. In each we become absorbed and are lost.

The period in which these works were made was one characterized by a search for fresh insight and meaning. Art was the one such conduit for this and Agnes Martin drew from Zen teachings; her work accepted and was absorbed within the chaotic void addressing it calmly. ‘Nature’s perfection lies in the absolute, blind freedom of units within it’

Yet order of some kind seems forever desired; why do we attempt to impose it? This speaks of a sense of discord within rather than without: By placing ourselves apart from nature while knowing ourselves to be fallible we internalize this sense of chaos and fail to acknowledge that since ‘nature doesn’t make mistakes’ it’s ok, there is harmony we just have to tune in.

I have paired a version of Stella’s ‘Morro Castle’ with an ‘Untitled’ Martin to draw attention to aspects of duality both within and between them: both are serious yet playful, both are the result of a rigorous, intentional and limited process, one still, the other active, one recedes the other advances: yet all in concordance.

Amazonian forest fire charcoal on paper.

Each 35 x 50 cm.

2022.

Available

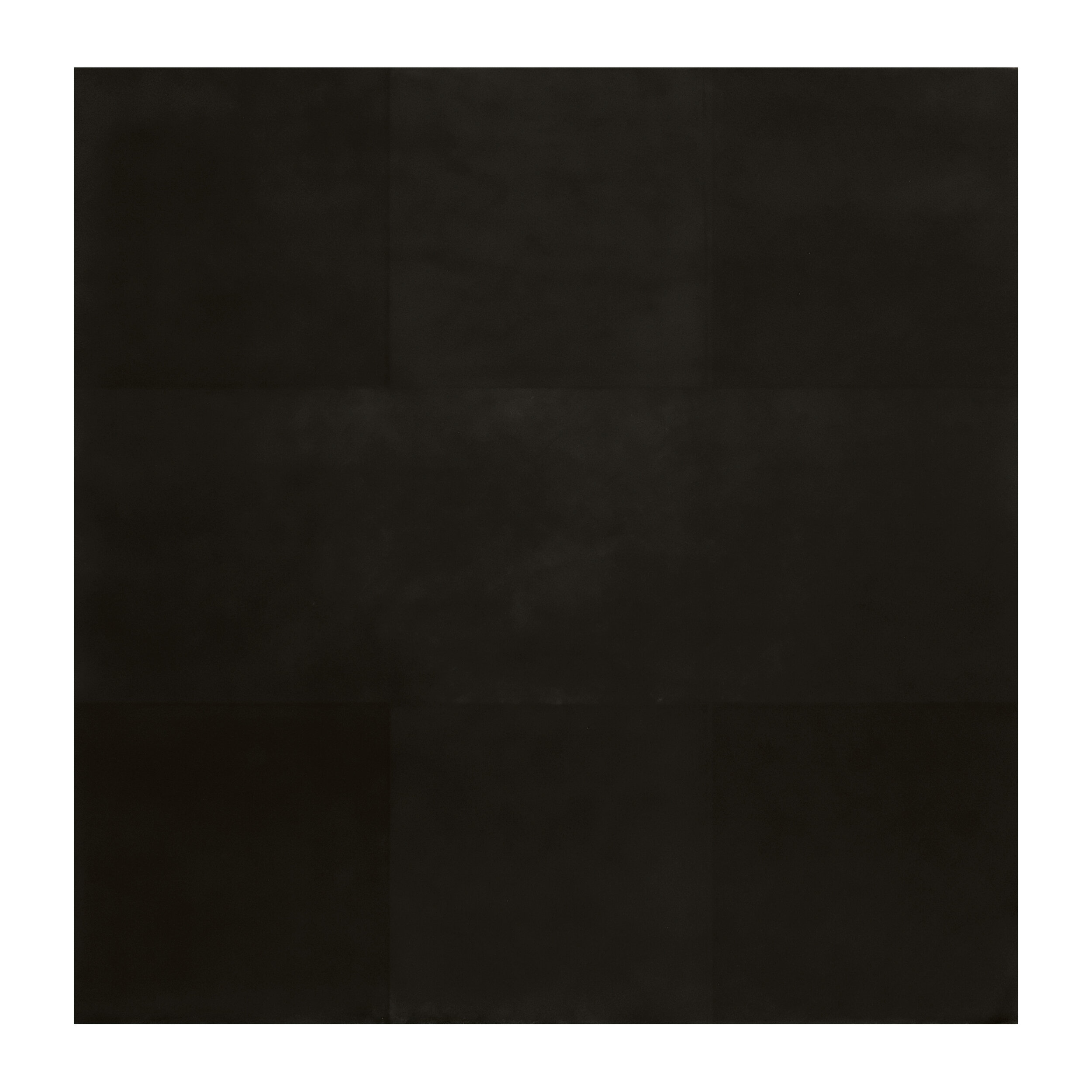

There is a heightened sense that we are living through ‘unreal’ times. This echoes T.S. Eliot’s remark that humankind cannot bear very much ‘reality’. And there is a concomitant sense of stasis, of being held beside time.

The resulting disorientation - spatial as well as temporal has caused many to contemplate the value of all aspects of life when all bets are off regarding what may constitute a future reality in comparison to the illusion of plenitude which preceded this period.

Reinhardt’s commitment to his Black Paintings from the mid ‘50s drew from his interest in both Asian and European mysticism and formed an enquiry as to ’how it might be possible to give hidden forces a kind of visible form, that was like the forces themselves; both present and not quite visible’. As a reader of Alan Watts, Reinhardt was familiar with his take on the coincidentia oppositorum / unity of opposites; e.g. that darkness and light are co-extant.

He was also aware of Watts reading of Dewey’s ‘Transactionalism’; esp re the ‘organism-environment’ in which one cannot separate an organism from its environment and vice versa: the subject (observer) and object (observed) are inseparable. Reinhardt’s aesthetic arrived at images that conjured what Walter Benjamin called the ‘aura’, that reaffirmed the lost kinship between subject and object: reunifying what habitual modes of perception differentiate.

This quality of ‘presence’ in Reinhardt’s Black Paintings derives from their being substantially insubstantial and this ungraspability reflects that sense that we are living in unreal times, of both being there and not being there, outside of time. ‘Underlying the Black Paintings is the idea of the void, the field in which action and non-action are one, and which holds in perfect equilibrium these apparent opposties’

Our disquiet in quiet times means that the void is once again present in all our lives. It need not be feared. Merely, it should be understood as ‘natural’ and ‘normal’ and we are all now existentialists seeking light in the dark.

Three types of forest fire charcoal on paper.

90 x 90cm

2022.

Available

This series grew out of a larger project called Canopy. That project has been growing in scope over the last three years since I first began using forest fire derived charcoal as a drawing material. The simple aim for Canopy is help restore and protect forests effected by fire by making and selling artworks which are made from the charcoal from those places: to fight fire with fire.

The History of the Black Square came about since I was searching for simple, universal and repeatable motif for Canopy – one that didn’t take, as The Tainted Sublime series did, over a month to execute each piece.

From Robert Fludd to Mark Rothko I have traced this history while Covid19 has spread like, yes, a wildfire, globally. It has felt an entirely appropriate body of work to make.

It is true that ‘there is no such thing as a good painting about nothing’. Rothko also said he ‘began to use pure black as a colour of light not as a colour of darkness’ and indeed neither Rothko nor I suffer from chromophobia.

What Rothko sought, above all, was to speak of the tragedy of the human condition and to create with his work a kind of stage within which this drama can be encountered; the viewer an active participant. ‘Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?’ Gauguin’s famous, eternal and tripartite question could equally be the title of any of Rothko’s late works but especially that of the South Panel in the Menil Chapel. This panel has the same dimensions as Rodin’s ‘Gates of Hell’. Rodin’s source is Ghiberti’s ‘Gates of Paradise’ and both derive from Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Rothko’s South Panel offers no answer to Gauguin’s title, no illumination because really there is no knowable answer, no certainty, only the void from when we came and to which we will return.

However, I wanted to offer at least a glimmer of light and so the history of the black square as it draws near to a close is with a black square framing a hint of perhaps better times that may lie beyond these tragi-comic times. While there are further black squares after Rothko there is a finality to his Menil Chapel works. In my last piece there is also an inversion of the Robert Fludd image with which I began this series.

Charcoal and pigment on paper.

150x100cm.

2022.

Available